According to Jewish tradition, one observes mourning rituals for the following relatives: father, mother, sister, brother, son, daughter, and spouse. One may choose to observe some or all of the rituals for other loved ones as well.

I. Aninut – Standing In-Between: From Death to the Funeral & Burial

Upon hearing of the death of a person it is customary to say, Barukh Dayan Ha-Emet, “Blessed in the True Judge.” This is also the time when one may tear his/her clothing (k’riah) as a sign of grief for the loss of a relative. While an onen (literally one “standing in-between”), a person’s focus should be on preparing for the funeral, including being in touch with a local funeral home, rabbi, or synagogue professional. The funeral home will usually arrange for shomrim (people to watch over the body) until the burial. The body will also be ritually washed (taharah) and wrapped in white shrouds by members of the sacred burial society (chevra kaddisha). Care for a deceased person is called hesed shel emet, “true kindness,” as it can never be repaid by the individual who has passed away.

II. Levayah – Accompanying the Deceased: The Funeral & Burial

The levayah (literally “accompaniment”) should ideally occur as soon after the death as possible, allowing for family to travel and other logistical considerations. Ask a rabbi for help in planning the service, whether graveside or in a synagogue or funeral parlor. The liturgy for a Jewish funeral service is usually brief and includes the recitation of appropriate psalms, the memorial prayer known as El Mali Rahamim (“God Full of Compassion”), a eulogy (hesped), and the special Mourner’s Kaddish. It is considered a mitzvah (sacred deed) to participate in shoveling some dirt on the coffin after it is placed in the grave so that the deceased person is laid to rest by family and friends. Mourners leave the graveside first, and others say to them the traditional words, “May the Omnipresent comfort you among all the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem.”

III. Shiva – Seven Days of Intense Mourning

Following the burial, the mourner returns home (or to the home where he/she will mourn) for a meal prepared by family and/or close friends. A yahrzeit (remembrance) candle is lit and mirrors are covered, and the mourner sits on a low chair. Throughout the shiva period, one remains home, limiting his or her attention to matters of physical appearance (some people do not bathe, shave, or wear new clothes) or any other distracting tasks, focusing instead on remembering the deceased person and mourning their loss. Visits, prayer services, and meals are arranged in the mourner’s home by family, friends, and community members. If one is a part of a synagogue or minyanim (prayer groups), there are often standing committees to help with such matters.

IV. Ending Shiva – Stepping Back into the World

Shiva customarily ends after the morning prayer service (Shacharit) on the seventh day of mourning. The final act of the shiva period to have one’s family, friends, and rabbi join them for a brief walk around the block. It is the first opportunity for the mourner to begin reentering the world. The concrete act of physically stepping outside, walking around the block, and returning home also communicates that one’s relationship with the house can now be renewed. This represents another step in the journey of aveilut (mourning).

V. Shloshim – 23 More Days of Grief & Return

Recognizing that mourning is an unfolding process, shloshim (literally, 30) is the next stage of grief. This period is designed as a partial reentry into one’s normal routine. People return to work and other responsibilities, but continue to observe some mourning practices. This includes reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish daily for all family members, and avoiding public celebrations. Some people do not cut their hair or shave. It is at the conclusion of the shloshim that one grieving a family member other than a parent officially ends his or her mourning. Some people arrange for the study of Mishnah (early rabbinic teachings) or other sacred materials during this period in honor of the deceased person.

VI. The Unveiling – Creating a Lasting Memorial

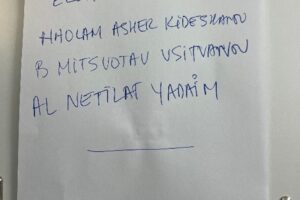

Within the first year after the passing of a loved one, mourners and their family and close friends gather at the gravesite for a brief ceremony called the Unveiling, which includes the uncovering of the headstone (matzeivah). Many people carry out this ritual in the latter part of the year of mourning. As with the funeral, this is an opportunity to eulogize the deceased person and to offer prayers for the repose of their souls. Before leaving the gravesite, it is customary to place rocks or pebbles on the headstone as a symbol of the enduring memory of the deceased person. Whenever leaving a cemetery, it is customary to wash one’s hands as a way of separating life from death.

VII. Yahrzeit—One Year Anniversary of Death

On the anniversary of the death of a loved one, it is customary to light a yahrzeit candle to honor their memory (beginning at nightfall), and to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish at each of the three daily services: Ma’ariv (Night), Schacharit (Morning), and Minchah (Afternoon). There are four occasions during the year when one can also recite the Mourner’s Kaddish in synagogue as part of the Yizkor (Remembrance) service: Passover, Shavuot, Shemini Atzeret, and Yom Kippur. It is common for synagogues to light the nameplate of the departed person on their yahtzeit, and of all of their deceased members on days when Yizkor is recited.

Additional Resources: