At Breaking Matzo, we often talk about the 3 M’s: Magical, Meaningful and Memorable as keys to an extraordinary holiday experience. There is a fourth M that you should consider when planning your next holiday celebration: Musical.

Song and dance add an element of joy and cheer to any occasion. Music can touch our hearts, stir our souls and stimulate our minds. The history of the Jewish people has long been suffused with music. Music helps us remember the past, helps inspires us for the future and helps us enjoy the present.

Since time immemorial music has played a central role in Jewish tradition. What bar/bat mitzvah would be complete without dancing the Horah? How many celebrations are made all the more joyous by the playing of Hava Nagila? How many smiles have been caused by the timeless tunes of Fiddler on the Roof?

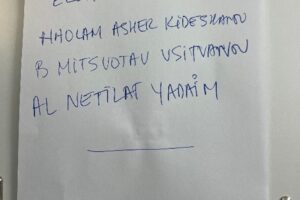

Music is not just for celebration; it is an important part of Jewish worship as well. During synagogue services a great many of the prayers are not simply said, but sung. Different temples have their own unique melodies and cadences to the same prayer songs. Across the Jewish diaspora and through the centuries the Jewish people have weaved a kaleidoscopic tapestry of music steeped in culture and history.

Music has a particularly important association with Passover. In Exodus after the children of Israel escaped from the Egyptians through the parted sea and arrived safely on dry ground, Miriam took out her timbrel and led the Israelite women in song and dance to celebrate. This celebration resulted in the bitter water becoming sweet for the children of Israel to drink. The power of music serves to unite and sustain the Jewish people during their hardships, a theme that has carried on through the eons.

We are excited to bring to you a new and powerful way to experience the musical nature of Passover: Teiku!

Teiku is a musical collaboration created by Josh Harlow and Jonathan Barahal Taylor. In keeping with the theme of Passover, their music is organized thematically around liberation and deeply connected to their ancestral roots. Teiku performs creative music arrangements of unique family Passover melodies, setting them in a modern context dedicated to exploring texture and improvisation. Teiku features Jonathan Barahal Taylor (drums and arrangements), Josh Harlow (piano and arrangements), Peter Formanek (saxophone and clarinet) and John Lindberg (bass).

Josh Harlow is a talented composer, pianist, keyboardist and music teacher. He has collaborated with numerous musicians and is a part of variety of musical groups including Teiku and the instrumental psychedelic band Submerser.

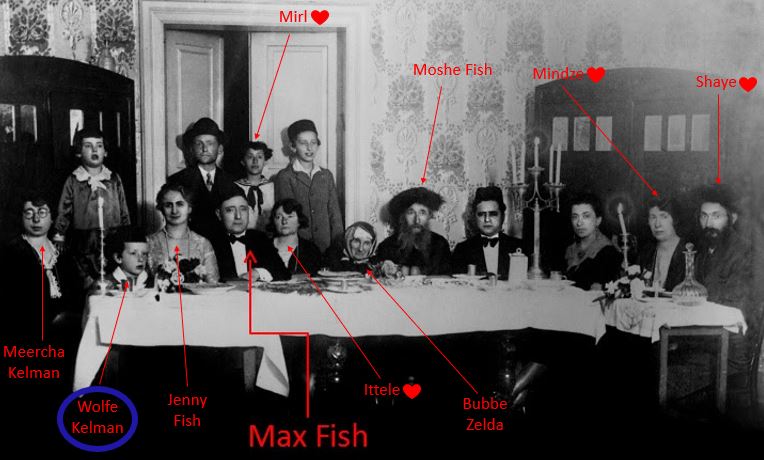

Josh grew up singing unique Passover melodies with his family at the seder table every year. His ancestors were Jewish-Ukrainians that had passed their holiday music through the generations and brought it across the Atlantic ocean with them. One day he was talking to his bandmate Jonathan Barahal Taylor about these songs. Jonathan explained that his family were also of Jewish-Ukrainian descent and they too had unique melodies they sang for Passover. They decided to research their ancestry and their family’s music. They were able to find their ancestral villages in modern-day Ukraine, but the songs were unique to their respective families.

Josh and Jonathan were so inspired by their families’ heritage and music that they decided to form a project to document, perform and breathe new life into these beautiful old melodies. They named the project Teiku, which means “Unanswered question” a symbol of how both musicians and Jews are always striving to learn and discover new things, combining old traditions with new ideas and concepts.

You can experience the magical, meaningful and memorable music of Teiku for yourself from the comfort of your own home. Teiku is hosting a live virtual spectacular to celebrate Passover on In Live. This one-of-a-kind performance will feature a mix of livestreamed music, music video, interviews, and dialogue to create an enriching and uplifting experience. This event has it all: beautiful music, inspiring history and spiritually fulfilling cultural content. There are opportunities for you to participate in the performance directly and possibly even sing with the band live!

This unique celebration of Jewish heritage, music, family and Passover traditions new and old is happening at 8:30PM (EST) on March 20th2021.

This blending of classic music with modern twists is a wonderful way to celebrate Passover together with the broader Jewish community during this time when we must be physically apart.

You can buy tickets to this remarkable event here.

You can learn more about Teiku here.

The Teiku live stream is powered by In.Live, a company focused on helping creators like Josh connect live with their communities worldwide. In.Live’s co-founder Eswar Priyadarshan is a 20-year friend and collaborator with Andy Goldfarb, through many personal and professional endeavors. Eswar is also a Breaking Matzo blog author you can read his 2018 dispatch from Salonica, Greece here.