What does Judaism mean to you?

Below is Andy’s response to his niece Sophia’s request for a letter about the meaning of Judaism to him.

September, 2013

Dear Sophia,

Mazel Tov on your Bat Mitzvah! It is a wonderful tradition that you are sharing with generations and generations of Jews.

I apologize for the delay in responding to your Bat Mitzvah request. Discussing the meaning of Judaism is such a broad question and I really wanted the time to think. I love being Jewish. My love for Judaism has grown dramatically over time. My Judaism has also evolved as I have lived my life. It is not a static experience. I feel that Judaism has helped me celebrate the High points in my life even higher, and mitigated the Low points from becoming even lower.

The five key elements of attraction to Judaism for me are the following:

- Community / Tradition

- Jewish Holidays

- Torah

- Israel

- Sacred Time

Community / Tradition

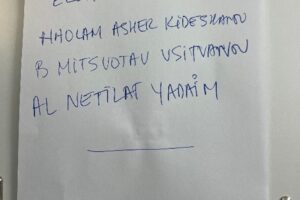

It is so meaningful for me observe traditions and rituals that Jews have shared for 5000 years. I am humbled when I read the torah which has existed for three thousand years. I feel priviledged to celebrate Passover and see the picture of our relatives celebrating in Poland in 1930! I feel connected when I sing the same songs in Synagogue (whatever form) with Jews around the world and share the same tunes. I have gone to synagogue in Tokyo, London, Paris, Venice, and Zurich. No matter where I have prayed and gathered, I feel as if I were in Allentown Pennsylvania (where I grew up) or Boston (Temple Israel). You can communicate in so many ways with Jews around the country and community. These are incredible opportunities to belong to a community. I also found Jewish celebrations to be a great way to meet friends in Boarding School and College. Attending High Holidays on campus was a great way to start the year and make friends.

Jewish Holidays!

Need I say more. I am so glad that you have experienced my love for celebrating the Jewish Holidays. I believe that the Jewish Holidays create many opportunities for Magic Memories. There are so many ordinary moments that can be transformed into Extraordinary experiences. With a little bit of effort, You can make the Jewish Holidays Magical, Memorable, and Meaningful!

Does anyone love Passover more than me? You know how much I LOVE Passover. I love the tradition of cooking together in our kitchen – my mom, daughters, and having so much fun. I love thinking all year about the Haggadah. The Seder dinner conversation is always so rewarding to hear what each of the kids have to say. The lessons of Passover “ordinary to extraordinary” “slavery to freedom” “focusing on the basics” “the succah of abundance and the succah of the wilderness” I could go on and on. I hope that you have enjoyed our celebrations at Seder. Of course, I love to compete for the matza eating contest and “who knows one?” with all challengers (Pablo watch out!)

Succot is so much fun to decorate a Succah and have a lot of food and wine. It is a graduation party for the jewish community for completing Exams/Graduation Ceremony of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. I love making a huge mess of oil in the kitchen as we cook Latkes and Sufganyot to celebrate Chanukah. There is something so magical about lighting the menorah for each of the eight nights. I also loved weekly Shabbat dinners when I grew up and when Caroline and Lucy grew up. It was a beautiful way to stop (Shabbat) and reflect on the week.

How could I possibly not mention Bar and Bat Mitzvah Celebrations and the coming of age for the Jewish Adult. You were able to enjoy Caroline and Lucy’s Bat Mitzvahs and see how meaningful it was for them to talk about their torah portions. Caroline referred to making Holidays (fun and celebratory) and Holydays (meaningful and spiritual) and the concept of Sacred time. Lucy talked about the transformation of Abram /Sarai to Abraham / Sarah as they brought “hay” G-d into their lives. (Today, I actually just reread their torah speeches and was moved to tears.)

It is important to me to gather Family and Friends (both jewish and non-jewish) for celebrations. I love sharing the traditions with the same friends year after year. I also love introducing non-Jews to our customs.

Last but not least, I LOVE THE FOOD in Jewish Celebrations. I love cooking and eating our traditional foods. Here are some of my favorites: chopped liver, chicken soup, charoseth (5 varieties), matza balls, kugel, schmaltz, latkes, sufganyot, hummantashen, etc…)

Torah

I love studying the Torah. I started studying with Rabbi Ulman in 2006. Caroline and Lucy began studying with him for their Bat Mitzvahs. I love studying with my family and friends. The torah has been around for almost 3,000 years. Why do people keep reading the same book? Why do other religions model their bible’s after the torah? Because, studying the torah is so impactful and meaningful. Each time I have studied torah, I have found it to be the most important thing I have done all week. The lessons I learn from each passage directly impact my life. I have been so deeply moved and influenced by my studies. The Torah deals with the essence of human beings and how to live a deeply meaningful and purposeful life. I love the interconnectedness of the Torah – elements and concepts cross across many chapters. Studying torah can be done at multiple levels and still have major meaning. Frankly, I don’t think that it matters whether or not you actually believe in the characters or stories in the Torah. You can purely read it as an example of the most successful piece of literature ever written.

Israel

Have you been to Israel? If you have, you understand why it is so powerful and meaningful and why it is most special place on the planet. If you haven’t yet been, please go! (There are many ways to go to Israel (Birthright) where you can travel very inexpensively to Israel with kids your own age.)

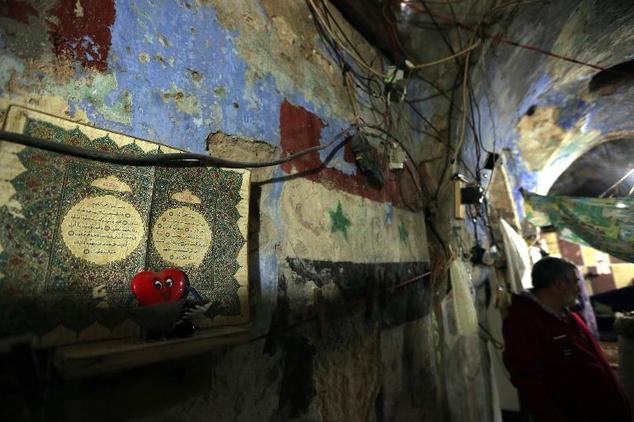

Simply put. Israel is the nexus of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. All three share their most important physical locations within 300 yards of each other. It is so powerful to see the center of all of these belief systems. Praying at the Western Wall and realizing that Jews have prayed at the very same spot for over 3000 years is a concept that it difficult for me to comprehend in my mind, yet immediately palpable in my heart and soul. The history and archeology will amaze and fascinate you. It is incredible to walk in the same footsteps that Jewish leaders have previously walked for thousands of years. In addition, the history of the founding of the modern State of Israel is so inspiring that a rag tag group of young Jews could build such a powerful military and economic and political country in the middle of a desert and in the midst of hostile enemies. Israel cannot never lose a war. If so, it would end the state of Israel. This concept is hard for us in the utopian United States to understand. Please go and visit your Israel relatives. It will be an unforgettable experience

Sacred time.

In Leviticus (Chapter 23 Verse 1), G-d teaches Moses about Sacred time and refers to Shabbat, Passover, and Succott. Shabbat literally means “to stop” These holidays help us reach a spiritual place by stopping our usual routine and being fully present. I have learned that the most important moments in life can last forever. However, this is only possible if you are fully present. I have learned that being fully present means experiencing time without any judgement or expectation. Simply being present to fully hear and experience the moment and share with those around you. Judaism has helped me reach this understanding. Judaism has enabled me to fully enjoy the emotional significance of Caroline’s and Lucy’s Bat Mitzvahs. In addition, Judaism has helped me deal with the difficult circumstances of death, divorce, and disappointment.

I actually first experienced this power of Judaism when I was an exchange student (age 15) in Japan. I was visiting Mazda Motor Corporation and staying in the company dormitory when my Dad told me on the phone that my grandfather (Normy) died. I was so grief struck and felt desolate and alone – completely by myself and in Japan! I left the dorm and wandered for hours and hours in the parking lot chanting all of the Hebrew prayers and Jewish songs that I could remember. I suddenly didn’t feel alone. I felt a connection to my family and friends and community and felt connected with Normy. I experienced Sacred Time in a parking lot in Japan! This epitomizes this important Jewish Concept.

A few final thoughts that I would like to share. You can make Judaism your own. There is no “Pope” or higher authority determining “right and wrong” in observing Judaism. There is no cookie cutter way to celebrate and observe. As you have experienced with me, I bring a lot of personal touches and creativity into our celebrations. You can innovate and personalize in Judaism. The most important Jewish Celebrations take place in the home (Shabbat, Succot, Passover). Make it your own!

La Chaim! Mazel Tov! You are on the right path, Continue…

Love, Andy (a/k/a Rabbi Andy for today 🙂 )