During times of sadness, is it possible to run out of tears? How can you hold space for others?

During periods of sadness, I have wondered, “Is it possible to run out of tears?”

I explored the Torah for an answer.

The person who cried the most in the Torah was Joseph. He cried 8 times in the book of Genesis. We can learn a lot about Joseph and his evolving relationships with his brothers in these moments of tears. His first cry was when his brothers first met him in his new role as the powerful leader in Egypt after selling him as a slave many years before. “Joseph turned away from his brothers and wept. Then he returned and spoke to them, and he took Shimon from them and had him tied up before their eyes” (Gen. 42:24). Joseph refused to cry in public. He had to be alone to fully express his emotion. The second time he cried was even more dramatic in showing his resolve not to cry in public and hide his inner heart. This was when he first saw his beloved brother Benjamin. “Joseph hurried out, for he was overcome with feeling for his brother, and had to cry. And he went into a room and wept there. Then he washed his face and took control of himself, and said, serve the bread” (Gen. 43:30-31).

It is possible that Joseph wanted to allow his brothers to repent for their selling of him into slavery. If he had cried in front of them, they would have known who he was. Joseph withheld his true identity in order to really observe his brother’s emotional evolution. This enabled Joseph to hold space for his brothers and allow them their own emotional experience. Holding space means lending your courage and strength, and suspending your judgment. It means creating a safe environment for someone you care for to exorcise the hurt within them. Allowing his brothers to witness their authentic experience and reacting with love and acceptance was a powerful way of supporting them.

Joseph’s third cry was when he finally opened his heart and soul. This is the great climax of the Joseph story, the moment when he is confronted by his brother Judah, who tells him of his father’s years of grief and mourning. Joseph was so moved to hear that his father was still Alive, he dropped his shield of pretense and allowed a cathartic release of emotion. And Joseph could not control himself. To all those standing in attendance, he cried out, “‘Take every man away from me!’ So, there was no one else standing there when Joseph made himself known to his brothers. And his sobs were so loud that all of Egypt could hear, and they were even heard in the House of Pharaoh” (Gen. 45:1-2). He experienced a range of emotions. He held space for his brothers to repent and Grow. He then experienced new soul cries in the passage and released a flood of emotion.

Joseph cries and cries and cries and cries. And he no longer turns away and hides his face, no longer washes away his tears. He cries openly and without restraint.

Joseph experienced a range of emotions during Genesis and his crying reflected his emotional variability. His early tears were alone. His final tears were released in a flood of emotion. He had a variety of tears.

Not all crying is the same. I wondered about the nature of tears. Interestingly there are three types of tears. Basal tears flow continuously in order to keep the eyelids from sticking on the eye. Reflex tears respond when something gets in your eyes and the reflex tears help wash it away. The third type of tears are called emotional tears. They really come from the heart. Interestingly, unlike continuous and reflex tears which are entirely comprised of water, emotional tears contain stress hormones like cortisol and thus help carry our stress away. This discharge of stress hormones helps stimulate production of endorphins which helps relax the body and mind after a “good” crying bit. Many of us actually feel more relaxed and soothed after emotional crying.

In one of my guided meditations, I have learned that tears of sadness can help water the seeds of our future happiness. And that You will never run out of tears. May your unending tears freely flow and enable your personal garden to blossom.

“Only eyes washed by tears can see clearly.”

Rabbi Louis L. Mann

Other Resources:

http://parshanut.com/post/134927500711/an-ocean-of-tears-parshat-mikeitz

https://www.google.com/amp/upliftconnect.com/hold-space/amp/

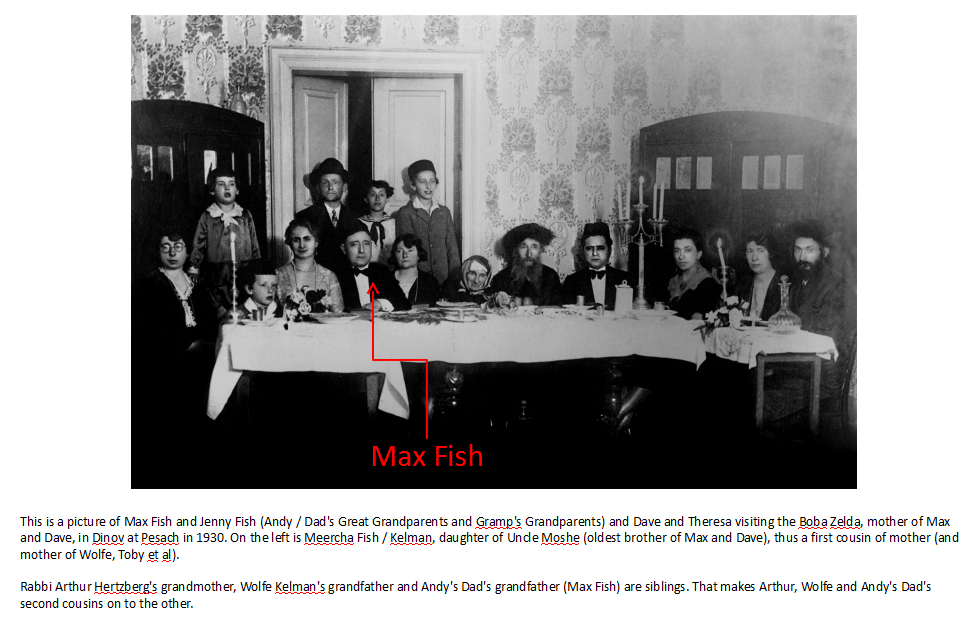

When my mom died I felt a tremendous sense of loss and I was overwhelmed with grief. I was so much at a loss that I completely immersed myself in the Jewish mourning traditions. The first step was to plan the funeral. This involved three activities: the funeral logistics, writing a eulogy, and assembling photos of my mom and of my family for a photo montage.

When my mom died I felt a tremendous sense of loss and I was overwhelmed with grief. I was so much at a loss that I completely immersed myself in the Jewish mourning traditions. The first step was to plan the funeral. This involved three activities: the funeral logistics, writing a eulogy, and assembling photos of my mom and of my family for a photo montage.