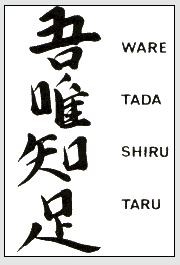

Faith, like folded flame,

Bends through time, still burning bright

Names reveal what be.

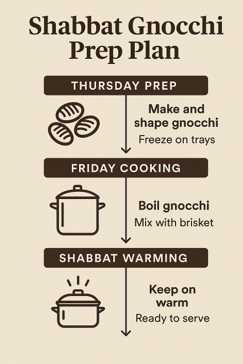

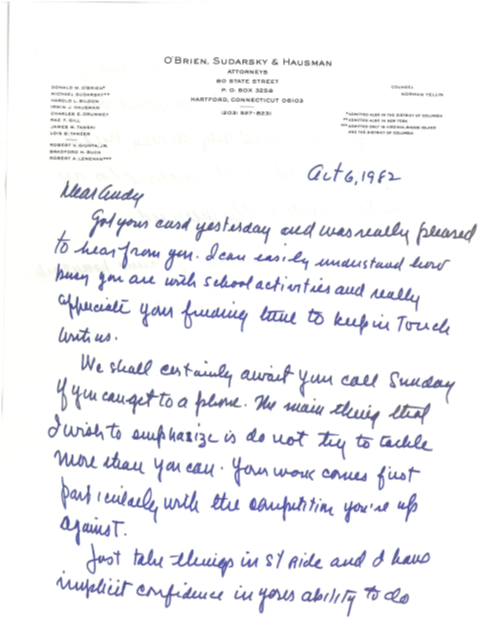

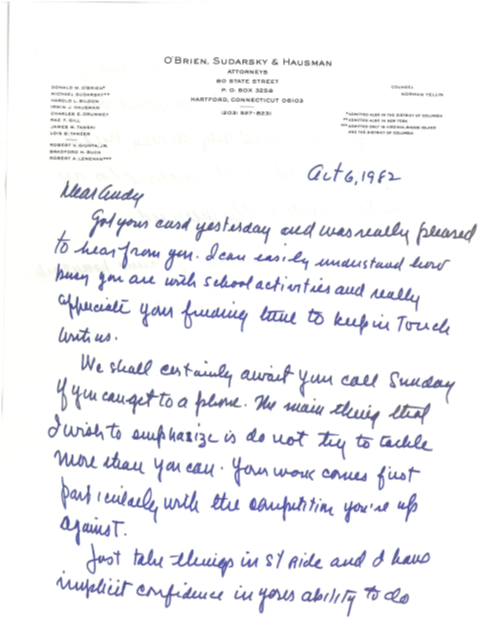

When I went to boarding school, my grandfather Normy would periodically send me a $20 bill with a handwritten note: “Here’s some lunch money for a pizza with your friends.” Pizzas only cost $5 at the time, but Normy knew I was struggling. Between the academic workload, being away from home, and the stress of growing up, his gesture was more than financial—it was spiritual nourishment. That extra portion of pizza carried an extra portion of love. I felt it deeply every time I opened Normy’s envelopes. (See the appendix for one of Normy’s letters to me from 1982.)

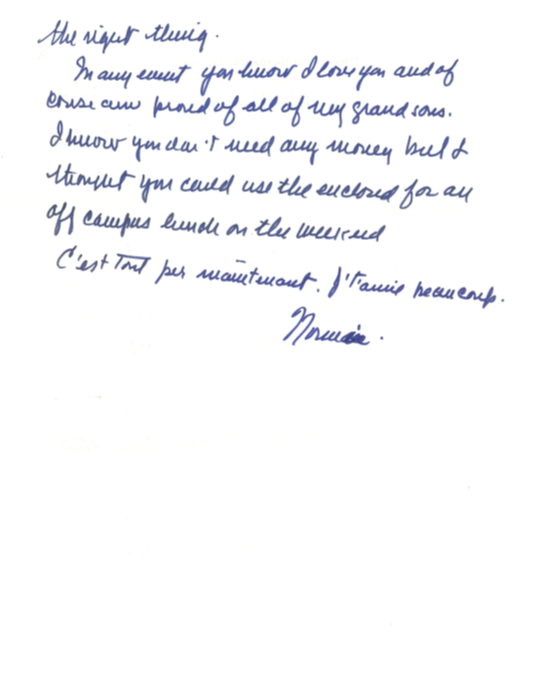

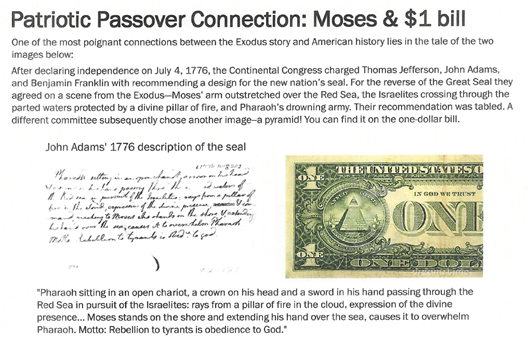

Years later, when I began leading Passover Seders for my children and their friends, I started giving dollar bills as a reward for finding the Afikomen. One day, I looked closely at the back of the U.S. $1 bill. There it was: an Egyptian pyramid. Intrigued, I researched further and discovered that our Founding Fathers felt a deep kinship with the story of the Exodus. John Adams once suggested the image of Moses parting the Red Sea while fleeing from Pharaoh as a proposed seal for the new nation—with the motto, “Rebellion to tyrants is obedience to God.”

In that moment, I realized that our spiritual founding fathers—Abraham in Torah, and Jefferson, Washington, Adams, and Franklin in America—shared more than vision. They shared faith.

When Moses asks God for His name at the burning bush, God responds with a phrase that is not a name in the ordinary sense: “Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh”—“I will be what I will be.” (Exodus 3:14). God is an unfolding presence—a verb, not a noun. In Jewish tradition, we often say “Hashem” (“The Name”), because God’s essence transcends definition.

This elasticity of God is what has sustained the Jewish people across centuries. It allows us to harmonize ancient rituals with modern life, to root ourselves in tradition while reaching for tomorrow.

It reminds me of a gymnast on a balance beam. The gymnast is constantly moving, adjusting, calibrating against gravity to avoid falling. Balance is not stillness; it is movement with purpose. Our faith in God is the same. It bends and flexes through grief and joy, always holding us aloft.

When our Founding Fathers wrote the Constitution, they did not just draft law—they drafted faith in the future. The longevity of the United States, the oldest representative democracy in history, rests on the Constitution’s flexibility. Article I, Section 8 includes what’s known as the Elastic Clause, which allows Congress to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper” to carry out its enumerated powers. It’s a statement of dynamic potential. Some truths emerge only over time.

Similarly, the Torah’s definition of God as “I will be what I will be” is the original elastic clause. Both the Torah and the Constitution are rooted in the belief that truth and adaptive authority must endure across time.

Most countries have one name. But both Israel and the United States carry dual identities. Jacob, our patriarch, is also called Israel. Jacob (“heel”) reflects a life of tension and transformation. Israel is the name he receives after wrestling with the divine: “You have struggled with God and with man, and you have prevailed.” (Genesis 32:29). He becomes Israel not by avoiding conflict, but by engaging with it—spiritually, morally, internally.

Likewise, the United States is both ‘United’ and ‘States.’ The Constitution holds the tension between federal authority and state autonomy. We are both: one nation and fifty sovereign entities. From the Federalist Papers to civil rights struggles, we have wrestled with this dual identity. Yet like Jacob/Israel, we have not broken apart.

The United Kingdom built an empire based on monarchy. The United States never aspired to territorial conquest. Similarly, Israel has given up land for peace. Both the U.S. and Israel are covenantal nations, not colonial ones. They fight wars not to expand, but to survive…to win battles and wage peace.

Freedom to worship was central to both stories. Avram left his father’s house and turned away from idol worship to pursue a covenant with the one true God. His embrace of monotheism laid the foundation for Judaism, and later Christianity and Islam. Like the Puritans crossing the Atlantic, Avram crossed into the unknown, guided by faith. In 1790, George Washington affirmed this ideal in a letter to Moses Seixas of the Touro Synagogue: “The Government of the United States gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance… Everyone shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.”

Founded in 1701, Yale University adopted the Latin motto Lux et Veritas (“Light and Truth”), but uniquely features the Hebrew phrase אורים ותמים (Urim v’Tummim) in its seal—a reference to the High Priest’s breastplate in the Mishkan/Tabernacle, symbolizing divine truth. This blending of biblical tradition and academic pursuit reflects the deep influence of Jewish thought in America’s founding.

Even the word ‘Hebrew’ (Ivrit / עברית) means ‘to cross over.’ From Noah’s Ark to Moses’ basket on the Nile to the parting of the Sea of Reeds, water crossings are rebirth moments. So too, Columbus, the Mayflower, and George Washington crossing the Potomac echo biblical voyages. The U.S. and Israel sail forward with sacred adaptability—transcending the present by honoring the past to reach the future.

There is another tradition from Normy that I passed to my children. In addition to treasuring his letters, I carry his favorite saying close to my heart: “Don’t let anyone rain on your parade.” It was Normy’s way of teaching me to have faith in the future and overcome short-term storms. As I reflect, it’s become my personal elastic clause, a phrase I’ve passed on to help my children navigate their own seas of uncertainty. Like the U.S. and Israel, Normy taught me to weather storms without losing spirit, to keep marching forward, even in the rain.

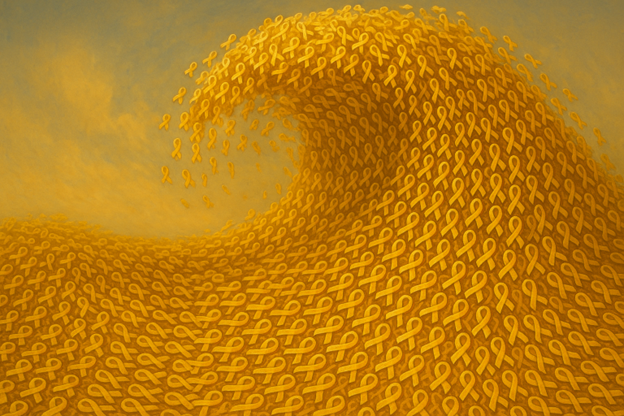

With belief in one God sparked by Avraham, carried by Moses who led the Children of Israel out of slavery, and lived through Jacob who became Israel, our people’s soul was forged through faith and perseverance. Across millennia we have endured: from Amalek to Pharaoh, Babylonian exile to Roman rule, Greek persecution to Ottoman oppression. Still we stand.

The American Revolution was also a triumph against the greatest empire of its time. Both Israel and the U.S. were born in defiance of tyranny—two divine Davids rising up against recurring Goliaths. Sustained by faith. Strengthened by struggle. And anchored in hope.

Perhaps that is the ultimate bond between Israel and the United States: not merely a strategic alliance, but a shared soul. Two peoples with dual names, eternal covenants, and sacred struggles. Each carrying faith like a torch: sometimes flickering, never extinguished.

Haiku:

Two names, one purpose—

Jacob wrestles, States unite

Faith bends but holds fast

Appendix:

This is one of my grandfather Normy’s letters to me from 1982.

Appendix / Further Reading

John Adams

Yale Emblem

Founded in 1701, Yale University adopted the Latin motto “Lux et Veritas”—Light and Truth—but uniquely embedded in its official seal is the Hebrew phrase “אורים ותמים” (Urim v’Tummim), meaning “light and perfection,” a sacred reference to the Kohen Gadol’s breastplate used for divine communication in the Mishkan (Tabernacle) at Shiloh, beautifully linking Yale’s intellectual pursuit of truth with the biblical tradition of spiritual insight. A nod to the deep influence of Jewish thought in America’s founding.

Touro Synagogue / George Washington

In the early 17th century, the Puritans set sail aboard the Mayflower seeking freedom to worship without persecution, founding the Plymouth Colony in 1620 and later the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Their exodus from England was inspired by a deep spiritual conviction—echoing the biblical journey of the Israelites from Egypt. For the Puritans, America represented a new promised land, a place to build a covenantal society rooted in faith and moral law. Their legacy helped shape the foundational ideals of religious liberty that later guided the American Revolution and still echo in the spiritual kinship between the United States and Israel today.

UK Empire Aspirations

In 1982, the long-standing sovereignty dispute between the United Kingdom and Argentina over the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) erupted into a 10-week war after Argentina’s military invaded the British-held territory in the South Atlantic. Britain responded swiftly, reclaiming the islands and causing significant casualties on both sides—255 British, 649 Argentine, and three Falkland Islanders. Though the military conflict ended on June 14, 1982, the diplomatic standoff persists into 2025, with Argentina still asserting its claim and Britain maintaining its position based on the islanders’ right to self-determination. The emotional resonance of the conflict extended even to the tennis world: in 1983, Argentine tennis stars Guillermo Vilas and José Luis Clerc—both ranked in the world’s top five—boycotted Wimbledon in protest of British control. Geographically, the Falkland Islands lie about 300 miles (480 km) east of Argentina and nearly 8,050 miles (12,955 km) from the United Kingdom, underscoring the enduring tensions over this remote archipelago.

- 1. Moses Seixas’ Address to President Washington

(Yeshuat Israel, Newport, 17 August 1790)

To the President of the United States of America. Sir:

Permit the children of the stock of Abraham to approach you with the most cordial affection and esteem for your person & merits — and to join with our fellow Citizens in welcoming you to Newport.

With pleasure we reflect on those days — those days of difficulty, & danger, when the God of Israel, who delivered David from the peril of the sword, — shielded Your head in the day of battle: — and we rejoice to think, that the same Spirit, who rested in the Bosom of the greatly beloved Daniel enabling him to preside over the Provinces of the Babylonish Empire, rests and ever will rest, upon you, enabling you to discharge the arduous duties of Chief Magistrate in these States.

Deprived as we heretofore have been of the invaluable rights of free Citizens, we now with a deep sense of gratitude to the Almighty disposer of all events behold a Government, erected by the Majesty of the People — a Government, which to bigotry gives no sanction, to persecution no assistance — but generously affording to all Liberty of conscience, and immunities of Citizenship: deeming every one, of whatever Nation, tongue, or language equal parts of the great governmental Machine:

This so ample and extensive Federal Union whose basis is Philanthropy, Mutual confidence and Public Virtue, we cannot but acknowledge to be the work of the Great God, who ruleth in the Armies of Heaven, and among the Inhabitants of the Earth, doing whatever seemeth him good.

For all the Blessings of civil and religious liberty which we enjoy under an equal and benign administration, we desire to send up our thanks to the Ancient of Days, the great preserver of Men — beseeching him, that the Angel who conducted our forefathers through the wilderness into the promised Land, may graciously conduct you through all the difficulties and dangers of this mortal life: —

And, when, like Joshua full of days and full of honor, you are gathered to your Fathers, may you be admitted into the Heavenly Paradise to partake of the water of life, and the tree of immortality.

Done and Signed by order of the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island, August 17th 1790.

Moses Seixas, Warden

You can view a PDF of the full address here.

- George Washington’s Reply to the Hebrew Congregation

(21 August 1790)

Gentlemen:

While I receive, with much satisfaction, your Address replete with expressions of esteem, I rejoice in the opportunity of assuring you that I shall always retain a grateful remembrance of the cordial welcome I experienced on my visit to Newport, from all classes of citizens.

The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet, from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security.

If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good government, to become a great and happy people.

The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy — a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights; for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my administration and fervent wishes for my felicity.

May the children of the stock of Abraham who dwell in this land continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid.

May the father of all mercies scatter light, and not darkness, upon our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in His own due time and way everlastingly happy.

Appendix: Elastic Faith and the American Founding

In the same spirit of elastic faith that allowed a fledgling people to adapt and endure, one of the American Revolution’s most extraordinary—and overlooked—contributors was a Jewish immigrant named Haym Salomon. Arriving in New York in 1775 on the eve of war, Salomon’s financial acumen and unwavering belief in liberty made him a critical financier of the Patriot cause. Working closely with Robert Morris and others, he helped secure loans and liquidity for the Continental Army when traditional sources of funding had collapsed.

Salomon repeatedly placed himself in danger. He was twice arrested by British authorities for espionage and personally underwrote large sums to keep the revolution alive at its most fragile moments. Many of those sacrifices were never repaid, and his contributions remained largely invisible to the public record.

His story embodies elastic faith at its highest level: faith that stretches beyond personal outcome, bends under historical pressure, and sustains both nation and spirit in service of a higher purpose—often beyond what the eye can see. The Torah does not promise that righteousness will be immediately compensated; it insists only that righteousness matters, even when it is costly.

In Jewish tradition, such lives are not footnotes to history. They are its hidden pillars.

For a fuller telling of this story—where elastic faith moves from idea to lived sacrifice—see The Forgotten Financier of American Freedom: The Story of Haym Salomon.