Have you ever received a message from a loved one who has passed away? What was the message? How did it make you feel?

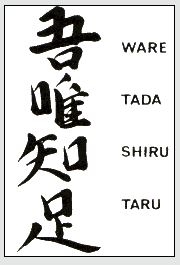

If we can have light without light, why can’t we have life without life?

Before my mom passed away, I never considered the idea of an afterlife. I was always purely focused on life — now and as we are. Since my mom passed away, I have become more open to the idea of an afterlife.

In writing this blog, I am aware that some may object to the idea of discussing an afterlife. I apologize in advance for any potential offense. This blog is my personal opinion and intended to help provide peace and meaning to those who have lost a loved one and are open to a continued connection.

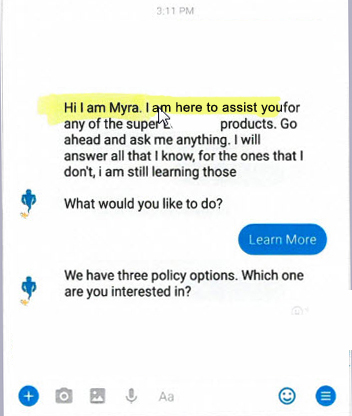

After my mom passed away, I began receiving messages from her. The first message was the last day of Shiva (Jewish mourning ritual) when I finished my walk around the block and returned to my office for the first time since her passing. When leaving the office that day, Friday, November 13, 2015, I saw the following image on TV, “Is Myra a good start?”. I was stunned and happy and smiled, (my mom’s name is forever Myra). I called my two brothers and amazingly we had all seen the same image on TV — at the same time!

I was really struck by this message. For the first time, I actually thought about Heaven. I really wondered what happened to my mom after she died. I realized that maybe her soul left her physical body. When I thought about my mom’s soul and the meaning of the message on the TV, I truly believe that my mom was telling my brothers and me that she was off to a “good start”. I began to imagine my mom on her way to Heaven. And, for the first time since she passed away — I smiled.

When reflecting upon my mom’s soul’s journey to Heaven, I remembered my eulogy for my mom when I quoted 2 Kings 2.

Elijah is about to die and go to Heaven. He asks Elisha if there is anything that he can give him. Elisha asks for a double portion of Elijah’s spirit. In my eulogy for my mom, I also asked for a double portion of her spirit.

1And it came to pass, when the LORD would take up Elijah by a whirlwind into Heaven, that Elijah went with Elisha from Gilgal.

9And it came to pass, when they were gone over, that Elijah said unto Elisha: ‘Ask what I shall do for thee, before I am taken from thee.’ And Elisha said: ‘I pray thee, let a double portion of thy spirit be upon me.’

Six months after my mom’s passing and after my first Passover without my mom, I had a transformative trip to Israel. During this trip, I received many messages and signs from my mom. I truly felt my mom’s communications and presence. It made me so happy and mollified my sadness at her loss. When I thought of these messages, I imagined that the holy and powerful nature of being in Israel is what brought about these connections with my mom. I really didn’t consider or imagine that my mom’s messages would continue.

Now over a year later, I continue to receive these messages. (I’ve included several more examples at the end of this blog).

When reflecting on these examples, I thought more about 2 Kings 2. I really contemplated Elijah’s going to Heaven in a whirlwind. Then I thought about my mom’s journey to Heaven. I realized that I did receive a double portion of my mom’s spirit. My mom and her spirit can exist in Heaven and with me and my brothers and grandchildren in our hearts.

When good things happen in my life, I think of the Talmud quote “Every blade of grass has its angel that bends over it and whispers ‘Grow, grow.’” I can just picture my mom in Heaven with angels saying, “How can we help Andy grow today?”

This prompted me to want to understand how could there be an afterlife. Could there be life without life? I immediately thought of Creation in Genesis.

3 Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light. 4 And God saw the light, that it wasgood; and God divided the light from the darkness. 5 God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. [b]So the evening and the morning were the first day.

14 Then God said, “Let there be lights in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs and seasons, and for days and years; 15 and let them be for lights in the firmament of the heavens to give light on the earth”; and it was so. 16 Then God made two great [d]lights: the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night. He made the stars also. 17 God set them in the firmament of the heavens to give light on the earth, 18 and to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness. And God saw that it was good. 19 So the evening and the morning were the fourth day.

God created light on the first day and called it good. However it wasn’t until the fourth day that God created the light of day and darkness of night with the sun, moon, and stars. So if sunlight was not created until the fourth day, what was the light of the first day? How could we have light without light?

I have learned that the day one light is that of goodness. Goodness needs no physical delineation. We simply know goodness.

I find a physical experience of this “light without light” concept when turning off a light bulb. Although the lightbulb is off, I can still see the light residue on my retina. I can still see the light in the dark.

When I pondered the idea of an inanimate object exuding energy after it is off to the afterlife, I realize the connection. If a lightbulb can generate light after it is turned off, why can’t a human body which has been on the planet 20, 40, 60, 80 years and made emotional connections with others generate life through our spirit after we are “turned off”?

I believe that if you have an open heart and a receptive mind, you may find messages from loved ones who passed away. If you come across a message, it may provide a beautiful moment to connect with a memory. Of course, if you are not open to making a connection, you will simply have the moment pass without a trace. However, if you are open and receptive, regardless of whether or not it is actually a connection with your loved one’s spirit, the feelings of connection with your loved one is real.

Additional Reading:

2 Kings 2 New JPS Tanakh 1917

Genesis 1:1

Additional Myra Connections

Myra License Plate:

On March 21, 2016, I informed my younger brother, Alex, that we reached an agreement to sell my mother’s house. While talking to Alex , I noticed the license plate of the car in front of me. At first glance, it appeared to say “Myra.”

Coincidentally, it was the 35th anniversary of my bar mitzvah. The significance of the anniversary, a time celebrating my spirituality with family and opening the door to a new chapter in my life, was a meaningful connection. Selling the house, closing one chapter of my life and opening a door to the next, made the license plate particularly meaningful, connecting to my mom…. I felt my mom was presiding over that day.

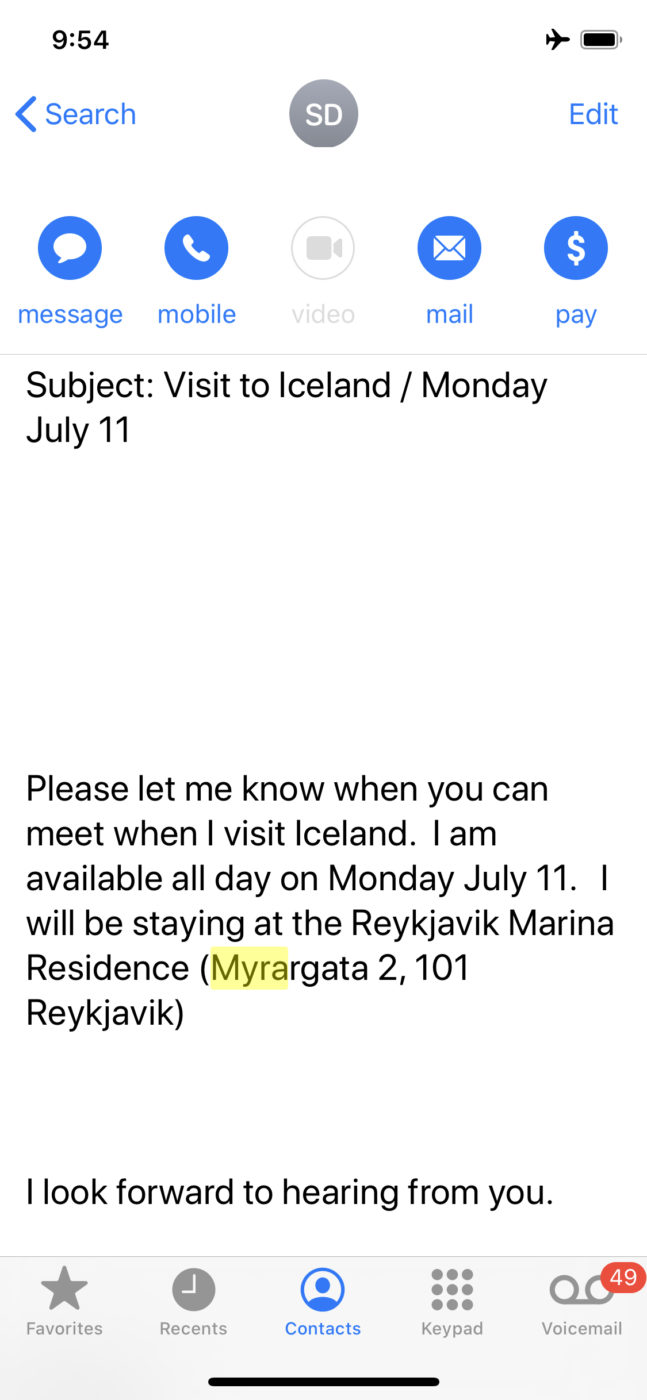

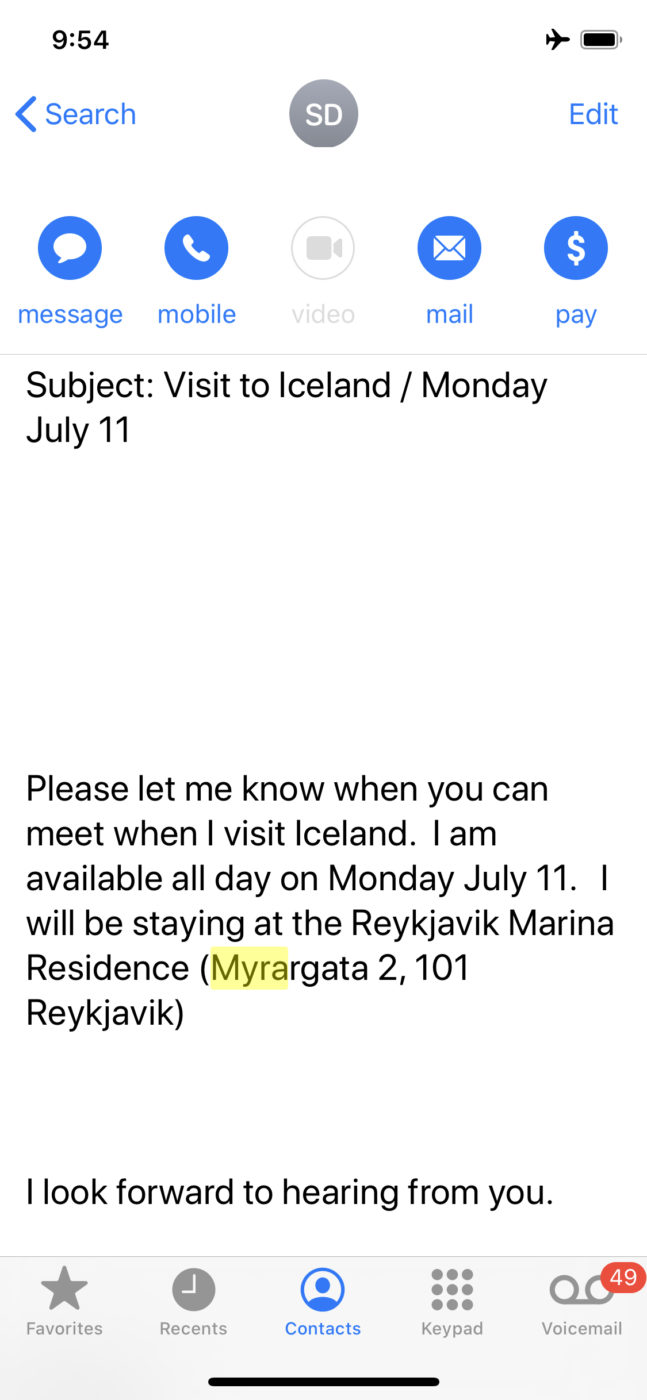

Nana Sign Iceland (July 2016):

On July 11, 2016, I had a business meeting in Reykjavik, Iceland. July 11 is my mom’s birthday. July 11, 2016 was my mom’s first birthday since she passed away on November 2, 2015. Please note the address of where I was to meet my business associate.

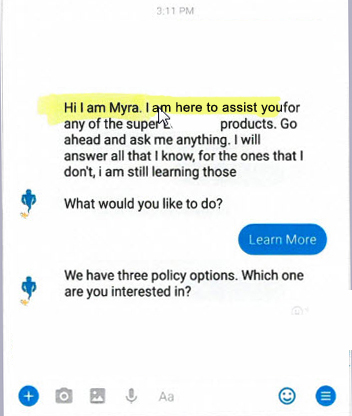

Nana Appeared in Business Meeting Materials (October 25, 2017):

I was attending a Board meeting for one of my portfolio companies based in India. It is in the customer service industry. Most of its customers are in India. I was so surprised to see that one of the customers they used as an example was named Myra! I smiled serenely.

The Nana Tattoo (December 8, 2017):

Relaxing by a pool in Miami, I ended up in a deep philosophical conversation with two guys from London, Steffan and Paul. After about an hour, Steffan stood up and removed his shirt to jump in the pool. I was simply stunned. He had a tattoo — which said “Nana”! I asked him why? Steffan was from Ghana and he explained that in Ghanaian, Nana means queen or king I simply smiled. I felt my mom’s presence…

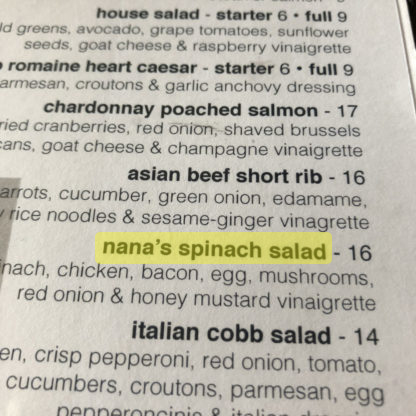

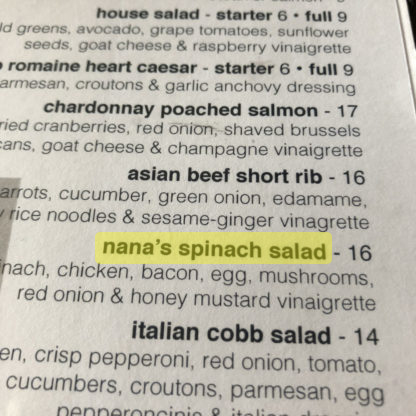

Nana’s Spinach Salad (April 6, 2018):

After a business meeting, I was looking for a quick lunch in Sacramento. My colleague and I wandered into the Foundation restaurant on L street. We sat down and perused the menu. It was immediately apparent what I would order for lunch. I stopped and smiled – “Nana’s Spinach Salad”. “Thank you mom. Hi mom. I know that you are in better place,” I thought to myself… My smile got wider and wider.

Myra Next to Me (June 2, 2018):

I was attending a concert for a work event. It was a very big night because one of my companies was launching a new product. I was excited and nervous. About fifteen minutes before the show began two women found their seats next to me. We had a brief exchange about the upcoming concert. Imagine my pleasant surprise when the woman next to me introduced herself, “Hi! Nice to meet you, my name is Myra”. I sat stunned and began to cry… I felt my mom’s hug and warmth on such a momentous night.

Tokyo Hana

Tokyo (March 2019)

I have been going to the same restaurant in Tokyo for over 32 years. In March, 2019, I had an important business dinner. When I arrived early for my dinner, I noticed the flower store across the street had recently changed its name to “Nana”. “Hana” means flower in Japanese so interpreted my mom telling me to stop and smell the flowers.

Text (April 2019)

We have a business customer. At a recent meeting, my team texted me about the new account person who joined our team. The new account person’s name was Nana!

Nana’s Treasures

Western Mass Jewelry Store (June 2019)

I have visited the same town in western mass for over 20 years. On my drive, I passed the same jewelry / antique store for each time. This past June, 2019, I drove by the same store and noticed it had changed the name to “Nana’s treasures” I stopped in to inquire. The owner told me that she just changed the sign a few weeks before to honor her grandmother.

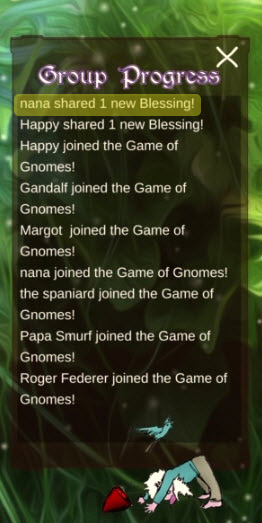

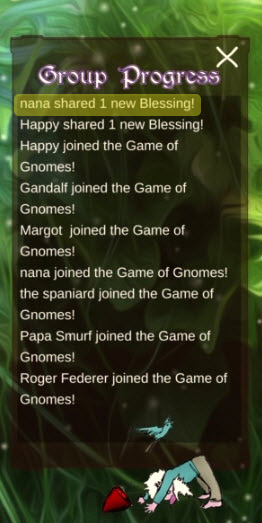

Nana sent you a blessing

Playing a mobile app (July 2019)

When I was playing a fun mobile app, a message popped up “Nana sent you a blessing” I was stunned! I asked my friends if anyone had used the name “nana” for their game “username” . A business colleague from Japan who was visiting said “yes. My childhood nickname was Nana” so I selected it as a player name.

Nana joined our team!

Birthday Greetings (July 2019)

On July 11, 2019, which would have been my mom’s 77th birthday, I saw this license plate in front of me. Mrs G – Mrs Goldfarb!

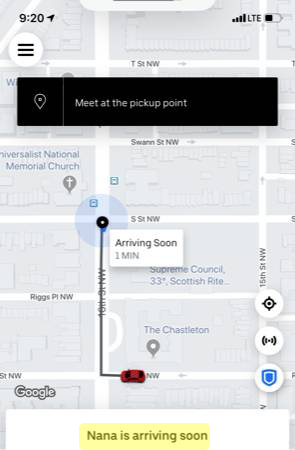

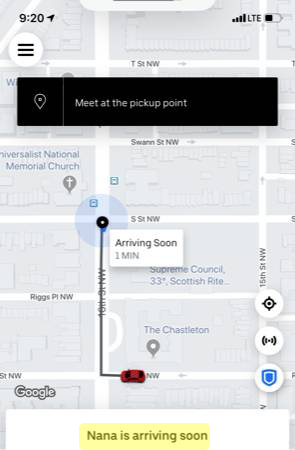

My daughter’s Uber driver (November 2, 2019)

The 4-year anniversary of my Mom’s passing.

Pelicans in my life! (February 2020)

My mom’s nickname for me was “pelican”. In 1985, my mom said that my middle initial “P” was not only for Philip but also for “Pelican”. My mom said I was like a pelican because the pelican is the only bird that can bite off more than it can chew, and handle it! In 1999, my mom gave me a steuben glass pelican, which I still treasure. I keep it on my desk.

This week I had two important business events. First, for Photo Butler, we were transporting equipment to Miami for a customer, and our team packed the equipment in a Pelican storage case! Then, at a Breaking Matzo photo shoot for Purim, the photographer brought his equipment in a Pelican traveling case! Both unbeknownst to me, and both this week!

The Sign From Pelicans From Professor Leshem (November 12th, 2020)

My mother met Professor Yossi Leshem a number of years ago as part of a bird watching and preservation conference in Israel. She wrote an incredibly moving article on the experience that you can read about

here. Yossi Leshem spoke at my mom’s memorial service in NYC in November 2016.

On November 12th, 2020 I was delightfully surprised to receive the following email and videos from Professor Yossi Leshem regarding pelicans:

Dear Friends,

Since the draining of the Hula Valley in the 1950’s, the draining of coastal swamps during the previous century, and the drying out of water sources along the pelican migration route in Turkey, Syria and Lebanon, Pelicans are fed in Israel reservoirs, in the Mediterranean lowlands.

They are fed with fish purchased by the Nature and Parks Authority and the Ministry of Agriculture. about 200 tons of fish every fall for the 50,000 migratory pelicans.

Once they feed, the Pelicans can continue to migrate to the swamps in south Sudan.

I am sending a presentation of a feeding in Bahan Reservoir: https://bit.ly/2ItIK6A

In addition, a number of videos, so that you will can enjoy the impressive feeding:

- https://bit.ly/36iwVIb

- https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=VCy_Kf7Otpw

- https://youtu.be/jVSMKMY20R0

Best regards, Keep safe,

Yossi Leshem

Myra at Hasty Pudding (March 5, 2020):

At the opening of the Hasty Pudding Theatricals 173 show, I attended with my daughter Lucy (who is Producer) and was surprised and delighted that the main character’s name was “Myra” enclosed is a video clip of the show. Given my mom’s love of the theatre and sharing the same name – Myra, I was also overwhelmed that the personality of the character was so similar to my mom as well. Myra (the character) and Myra (my mom) was dramatic, flamboyant, enthusiastic, and full of spice and energy. It was a truly fabulous night at the Theatre!

Myra License Plate (November, 2020):

Around the 5 year anniversary of my mom’s passing, my daughter Lucy sent me this photo of a license plate that she saw while driving.

Happy Birthday Mom:

I’m publishing this today, July 11, 2018 on what would be my mom’s 76th birthday. This photo was taken on July 6, 2013. Mom, thank you for helping me become open to so many new possibilities.

Now here is a picture of me with my own personal zenibachi in 2021.

Now here is a picture of me with my own personal zenibachi in 2021.