We hope these questions stimulate a meaningful discussion at your Passover Seder.

Q1: Passover is the story of the children of Israel leaving slavery in Egypt, wandering in the wilderness, and reaching freedom in the Promised Land.What are you a slave to today? Why?

We are all slaves to something today. Not physical slaves but slaves in our own mind.

Kids: What do you think about the most? You may be a slave to electronics, video games, or your favorite television show.

Adults: Are we slaves to our past? Or maybe slaves to worry, work, financial pressure, or scheduling?

Q2: What represents your Promised Land? What is freedom to you?

During Passover, we celebrate the story of the children of Israel seeking freedom in the Promised Land. But what does being free really mean to each of us?

Kids: You may feel really free during summer vacation, summer camp, sleepovers, walking your dog, or attending a sporting event. When do you feel most free?

Adults: What does freedom look like to you? When are you truly free? On vacation? Engaging in a special family activity? Cooking dinner with friends? Going for a long hike? Is freedom just having unscheduled time? Do you have a favorite activity when you feel most free in your mind and spirit?

Q3: What are your basics in your life? What are your extras?

Matzo is a very simple food. The word “matzo” in Hebrew means to “drain out”. Food at its most basic. Only flour and water, oil and salt. Matzo kept the children of Israel alive while they were fleeing slavery. Eating matzo makes us think about the basics in life. What do you really need to live your life?

Kids & Adults: What do you really need in your life? What do you really need to live your life?

Kids & Adults: What are the basics in your life? What are your extras?

Q4: If you had to leave home in the middle of the night, what would you bring with you?

When the children of Israel fled Egypt, they had to leave in the middle of the night and without much time to prepare. And they couldn’t take many possessions with them on their journey. There were difficult choices about what to bring with them from their homes.

If you had to escape in the middle of the night, what would you bring? (These can be physical or emotional keepsakes).

Kids & Adults: What would you take from your house in the middle of the night if you had to leave?

Q5: Who would you like to sit in Elijah’s chair at your Seder?

Elijah is the prophet who never died. He is viewed as eternally returning to help the poor and assist those in need. When we believe in Elijah, and invite him to join us at the table, we receive a special gift or blessing because we can imagine him and his good deeds.

The special cup for Elijah, and in some families a chair for Elijah, is a reminder to invite spirit of generosity and goodness to join us at the Seder.

In some families, the children go to the door and open it for Elijah so that Elijah, or another good soul, can enter. (See footnotes below for Torah references)

Kids: Who is missing from our table this evening? Who do we need to invite in?

Kids & Adults: What special person would you most like to share tonight’s festival meal? This person can be alive today, or not. It might be a friend, relative, or someone that you would like to meet. Please share who this person is and why you would like to share tonight’s Seder with them.

Adults: Whom do we need to help us complete our journey from “slavery” to “freedom”? Who helps each of us become complete? Who or what do we need to lead us on our journey to freedom?

Q6: The Afikoman is created by breaking an ordinary piece of matzo. What is something ordinary that has become extraordinary for you?

We think a lot about transformation from the ordinary to the extraordinary during our Seder.

A good example is the Afikoman. We ate matzo at the start of our journey out of slavery, but during the Passover Seder, we transform this simple humble food. We take one ordinary piece of matzo and by breaking it in half, it becomes an extraordinary piece of matzo: the Afikoman.

One example of something ordinary to extraordinary in my life is my family’s antique brass hand washer. I received it as a gift from my grandmother, Helen Fish Goldfarb. Her father, my grandfather Max Fish received it from his father (my children’s great great great grandfather Moshe Fish). It is from the late 1800’s in Dynow Poland and has been used for Passover in our family for over 100 years. Perhaps your family has an artifact or heirloom that has been handed down over the generations, layered with the history of your family, and so has become “extraordinary.”

What is something ordinary in your life that you have transformed into something extraordinary?

Kids: Is there something special you have transformed in your life because you love it so much? Maybe a special blanket or doll? Or something you received from a special relative, or is it something you made? Something you have transformed by how much you love it and need it?

Adults: How do you know that it has become extraordinary? Do others or just yourself know this transformation? Do you have a “public” Afikoman and a “private” Afikoman?

Q7: Dayenu means “enough”. It is an expression of gratitude. When was a time in your life that you truly experienced Dayenu? And expressed gratitude?

In Hebrew, Dayenu means “enough for us”. We both sing it and say it many times during the Seder. Dayenu can be an opportunity to recognize that you put forward your best efforts. Or, that you received a bountiful offering from someone else.

On one level, Dayenu speaks about giving thanks to God for delivering the children of Israel into the Promised Land. On another level, it is a message about setting limits on our expectations. Dayenu is about learning to be satisfied and grateful with what we have received.

Kids: Can you think of a time when you received something in your life that you are grateful for?

Adults: Was there a time in your life that you didn’t experience Dayenu, when you didn’t appreciate that you had received “enough,” but should have?

Q8: Miriam led the Children of Israel in celebration after crossing the Reed Sea (Sea of Reeds). What does it mean to be someone who leads other in rejoicing? When have you ever danced for pure joy to celebrate? How did it feel? What was the response of the group to your dance?

In Exodus after the children of Israel escaped from the Egyptians through the Parted Reed Sea and arrived safely on dry ground, Miriam took out her timbrel and led the Israelite women in dance and song to celebrate. This celebration also resulted in the bitter water becoming sweet for the children of Israel to drink.

When I was in Israel for my daughter’s Bat Mitzvah at a restaurant on the Lake in Tiberias, there was another family’s Bar Mitzvah celebration, and I impulsively crashed the party and led my family in dancing the Hava Nagilah with the rest of the party. It was so much fun!

Kids: When have you started a really fun celebration dance with your friends? What was the occasion? How did they react?

Adults: When have you really let loose for pure celebratory dance? I always think of the fun of dancing the Hava Nagilah and raising the Chair at weddings and Bar/Bat Mitzvahs.

Q9: The Reed Sea (Sea of Reeds) was the final obstacle for the Children of Israel to overcome in escaping Slavery. What is your personal Reed Sea (final) obstacle in your journey from Slavery to achieve Freedom?

When the children of Israel escaped from slavery in Egypt, they faced one final obstacle before reaching freedom. They had to cross the Reed Sea. In Exodus 14:15 God tells Moses that the children of Israel are to go forward. They are being asked to take the first step. And what is the first step? To walk towards un-parted waters. It is an act of faith that proceeds God’s act of liberation. And so it is with our lives. The first step is ours. Then Moses is instructed to raise his staff and the waters parted, allowing the children of Israel to pass from the present-past into the future to truly cross over – Evrit is Hebrew meaning to “cross over.”

Adults: What has been your final obstacle as you have tried to escape from slavery, or break bad habit, or start a new relationship? How did you overcome the obstacle? Did you ever proceed without knowing the solution in advance?

Kids: Have you ever tried to do something new and had an obstacle? How did you overcome it?

Torah Passage: Exodus 14:12.

“Then the lord said to Moses, “why do you cry out to me? Tell the Israelites to go forward. And you lift up your rod and hold out your arm over the sea and split it, so that the Israelites may march into the sea and onto dry ground”

Q10: Passover can be viewed as an opportunity for a spring cleaning for the soul. What do you want to cleanse or remove from your life this Passover?

Passover has a fun tradition that embodies this idea: it is called “the search for chametz.” Chametz means leavened bread. During Passover, we give up all leavened products, eating matzo instead of these “puffy” foods. The word matzo derives from the Hebrew term for “drain out,” and consists of just flour, salt, and oil. Chametz, however, includes all of the extras—yeast, sugar, eggs, etc. Giving up chametz and eating matzo helps us focus on the basics in our lives and reflect on our ongoing journeys from slavery to freedom. You can read more about this search here.

Adults: What are your thoughts on Spring Cleaning these days? Is there Spring Cleaning of your house, your home, and your inner self that you may be interested in exploring during these days of awe? Have you found an opportunity to look at your physical surroundings in a different way? Have you looked inside yourself in a different way?

Kids: Have you ever found anything interesting or meaningful while cleaning?

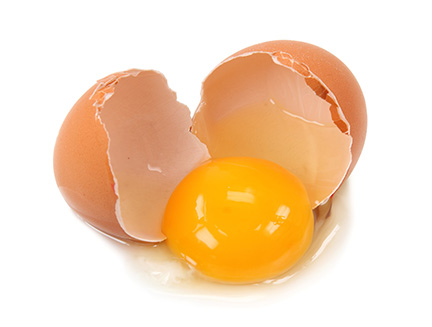

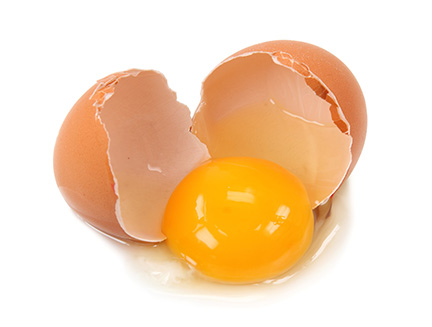

Q11: The roasted egg on the Seder plate can represent enduring through suffering or it can represent the fragility of life. Are you raw or are you ready?

During Passover, we discussed the meaning of placing a roasted egg on the Seder plate. A burnt egg can be interpreted to represent the suffering endured by the Hebrews during slavery in Egypt. The roasted egg also has a broken shell. This can demonstrate the fragility of life and hopefully inspire an appreciation for the blessed moments we’re given. At this year’s Seder, a friend who had never celebrated Passover asked me an interesting question: Do you boil the egg before it is roasted, or is it raw? It raised the thought: Are you raw or are you ready? Let’s explore the egg – in its broken form.

There is a context to whether or not a broken egg is good or bad. If you have a raw egg in the kitchen and you drop it, the egg shell breaks and the egg is lost. It is forever broken. You cannot simply gather the yolk and white and put it back in the broken shell. (As the nursery rhyme goes, Humpty Dumpty cannot be put back together again!)

However, there is another context when the broken egg shell is the not the end of life, but rather the beginning of life! If it is a baby bird hatching from its shell it is a beginning. A bird hatching is a truly celebrated event marking the evolution of life.

Adults: Are you in a raw state where your shell is delicate and needs full protection and security? Or are you ready? Ready to break out of your shell and enter the next phase of your life to encounter the world without a protective barrier.

Kids: What is something new that you think you’re ready to try this year?

Torah Footnotes for Dinner Table Discussions:

Torah references for Elijah and Elijah’s Cup

You have asked a difficult thing, he said. “If you see me as I am being taken from you, this will be granted to you, if not, it will not.” As they kept on walking and talking a fiery chariot with fiery horses suddenly appeared and separated one from the other, and Elijah went up to Heaven in a Whirlwind. 2 Kings 2:10-11, p. 77 JPS. Note: Elijah went up in a whirlwind” but it doesn’t say that he died.

The Connection to Passover and Parting of the Reed Sea: 2 Kings 2:13, p. 77 JPS

(Elisha) picked up Elijah’s mantle, which had dropped from him, and he went back to the Jordan River. “Where is the Lord, the God of Elijah? As he too struck the water, it parted to the right and to the left, and Elisha crossed over.”

These are references to Moses striking the rod and parting the Reed Sea, and the Israelites Crossing over the Reed Sea to escape slavery.

Torah Reference For Miriam’s Dancing Question:

Exodus 15:19-22, p. 146 JPS

For the horses of Pharaoh, with his chariots and horsemen, went into the sea; and the Lord turned back on them the waters of the sea; but the Israelites marched on dry ground in the midst of the sea. Then Miriam, the prophetess, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all of the women went out after her in dance with timbrels. And Miriam chanted for them “Sing to the Lord, for he has triumphed gloriously; Horse and drive he has hurled into the Sea.”

Shortly thereafter, when the Israelites, had only bitter water to drink, the Lord gave the Israelites Sweet and Potable Water.

Q12: When you’ve been faced with a difficult experience, were you able to learn something from it? Did you internalize these lessons and continue to grow afterwards? Or did you miss an opportunity to learn and grow?

In Exodus, the Hebrew slaves were given gold and silver by the Egyptians (Exodus 3:22). After crossing the Sea of Reeds, the Children of Israel (comprised of mixed multitude of Hebrew slaves and some Egyptians), used this gold and silver to build two objects: a Golden Calf (Exodus 32:4) and they also build the Arc of the Covenant (Exodus 25:11).

Some built The Golden Calf, an idol to worship in the instead of God, which greatly angered God. This demonstrated that some of the Children of Israel had lost their way, returning to idol worship, and giving up faith in God.

Others built the Arc of the Covenant. A box beautifully decorated with the gold and silver from Egypt. Inside they placed two sets of tablets containing the Ten Commandments, one set was written by God and broken by Moses while other was written by Moses and intact. They protected the Arc of the Covenant in the Wilderness and later brought it to the Land of Israel where it was placed in Shiloh for 369 years.

The Golden Calf was an object to worship and had no benefits and no lasting significance. The Arc of the Covenant was a vehicle to enable worship – not the object – but the lessons contained within. The lasting impact of the Arc of the Covenant has been significant – as we continue to honor the learnings it holds today.

Here are a few questions for your seder inspired by the biblical use of gold and silver, hopefully they inspire lively and thought-provoking discussions.

Adults:

- What is an example of your “gold and silver” (your learnings) from a difficult experience?

- Did you have an experience of creating a Golden Calf?

- When have you created an Arc of the Covenant with your learnings?

Kids:

- Have you had a difficult experience and learned something valuable?

- Have you even forgotten your lessons and made the same mistake again?

- What is an example of a lesson that you learned that you would never forget?

Spanish Sephardic Charoset

Spanish Sephardic Charoset