“Kids….go get your Hanukkah presents… under the Christmas Tree!”

These words are spoken each year on the first night of Hanukkah. Light the lights! Our Christmas tree lights reflect brightly on the Hanukkah presents wrapped tightly under the tree, as the menorah candles burn low, shining brightly in our kitchen window. The holiday is more about being present than having presents (after all we have the 25th of December to thank for that). We celebrate together exchanging presents and playing dreidel with chocolate gelt and we rejoice with singing “Oh Hanukkah, oh Hanukkah come light the menorah” and “Dreidel, dreidel, dreidel” as my kids roll their eyes and try desperately to silence me before I change the lyrics! Since my kids are little bit older now we choose to give them one present the first night (instead of 8). Usually it is an experience such as a concert or sporting event or gift cards to eat out with friends, perhaps a night of fun in Boston or NYC including dinner and shopping (for Christmas of course). It is a perfect time for us to be “present” as a family and enjoy some time together celebrating the magic of the holiday season.

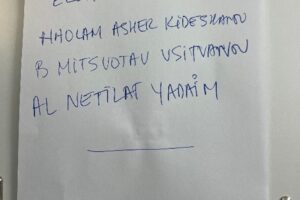

I was raised Jewish. As a kid, I celebrated Hanukkah with my family; my parents and two sisters. 8 nights and 8 lights we spent each night picking out our candles, singing our prayers while lighting the menorah, eating latkes with red apple sauce and opening one small present each night. A typical week (not a no school holiday) we attended school, ballet class and theatre rehearsal but always came home to celebrate each special night. I loved spending this time with my family, and year to year we celebrated the five of us, keeping our traditions alive and enjoying the holiday time together. When Christmas rolled around, we spent the holiday skiing up north and eating Chinese food -I always wondered what it would be like to celebrate both holidays?

Years later I met my husband. He was raised Catholic and 100% Sicilian. He brought traditions of his past and family heritage and together while we dated for over 7 years we celebrated both the Jewish and Christian holidays together. He came to my family home to experience a Traditional Seder, at Passover sitting next to my grandparents (survivors of the holocaust) and I went to his house to experience a traditional Sicilian Easter meeting his relatives from Italy (the food, ah….the food)! Christmas with his family and friends and Hanukkah with mine. Teaching each other about the holidays and incorporating them into our lives. It seemed every day was a Jewish or Christian holiday and there was always something to celebrate!

Elisabeth, her family, her sister and nieces picking out their tree!

Then we were married and had children. We discussed how we were going to raise our children and with our strong family bonds, our traditions (and our delicious food), both religions were to remain. We agreed it was up to us to teach our children the importance and meaning of all the holidays and the traditions we brought forth from our past. We discussed the similarities, and pointed out the differences… and realized, after all, many paths lead to the same god? Right? If you ask my children, I’m pretty sure they feel like the lucky ones. Celebrating both holidays with our families jewish or catholic, our backgrounds and religions have taught them how to respect others beliefs, despite their differences. It is the season of giving and that is what my husband and i have instilled in our children-making sure they know their holiday spirit can shine bright by sharing their joy, knowledge and traditions of all the holidays we celebrate, with others!

A traditional succah is created outside synagogues and homes as a place to invite family and friends to celebrate the fall harvest. A dining table is set up in our traditional succah to enjoy the harvest with food and comfortable seating for eating, entertaining and sometimes (as in our Moroccan Succah) even sleeping!

A traditional succah is created outside synagogues and homes as a place to invite family and friends to celebrate the fall harvest. A dining table is set up in our traditional succah to enjoy the harvest with food and comfortable seating for eating, entertaining and sometimes (as in our Moroccan Succah) even sleeping!