“Would you please wash your hands?” Joan asked.

“I always do,” I said.

“No, I mean, would you begin each morning by washing your hands?”

I didn’t understand. Washing my hands? I had done that my entire life. What could be so important about something so simple?

It was January 22nd, 2026, the yahrzeit of the Baba Sali, Rabbi Israel Abuhatzeira. I had written previously about Joan’s family and their connection to him. She told me that if I prayed to Hashem in his merit on that day and committed to begin a new mitzvah, I would invite blessing into my life.

So I began washing my hands each morning when I woke up.

“Did you say the blessing?” she asked. “Did you wear a kippah?”

I said no to both.

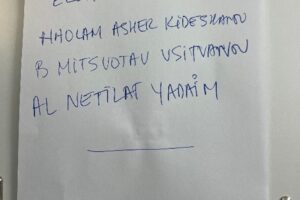

The next morning, she handwrote the prayer and taped it to the cabinet by the sink. I read it slowly. I did not fully understand the words. But I recognized one: yadayim — hands.

So I began.

On Shabbat, we were preparing to read Parshat Yitro and the giving of the Ten Commandments. Instead, our rabbi began with the battle against Amalek from the preceding section. I wondered why he was not speaking about Mount Sinai. Then he began to speak about hands.

Our rabbi explained that when Moses raised his hands, the Children of Israel prevailed. When his hands lowered, Amalek prevailed. Moses’ hands grew heavy and required the support of Aaron and Hur in order to remain raised. Even elevation is not sustained alone.

Why would victory hinge on the position of Moses’ hands?

The rabbi explained: lowered hands pull us downward toward the ground. Lifted hands position us toward Heaven.

As an aside, a boxer keeps his hands raised to protect himself. Active hands serve as a shield. But when hands rise above the head, one is exposed and vulnerable. To lift your hands in faith is to trust protection beyond yourself.

As a Kohen, I realized something more personal. Kohanim lift their hands to bless the people. In the Mishkan, Kohanim also washed their hands before entering sacred service.

I had written elsewhere about the posture of hands while eating: how slavery keeps them reaching downward, how the wilderness trains them to lift, how the Promised Land invites them to reach to the trees for the fruit and to the ground to plant the seeds. Now the metaphor was no longer theoretical, but embodied.

One morning at the sink, I paused over the word netilat in the blessing.

What does that mean? I wondered. I had always assumed it meant “washing.” It does not. It means “lifting.” Al netilat yadayim: concerning the lifting of the hands. Not merely washing, but lifting.

That is why the morning blessing can be a quiet echo of the Exodus. We do not bless Hashem merely “for washing” our hands; we bless for lifting them. It is the spiritual start of the day.

Sleep can feel like a kind of slavery, a temporary surrender of awareness. Waking is a small liberation. When we rise, we wash as though passing through the Sea of Reeds. As we climb out of bed, we enter a wilderness moment, uncertain and unscripted, and lift our hands in praise. At the sink, we receive a silent Sinai. Then the day stretches before us like a Promised Land.

The Promised Land resembles the fullness of the day: work, responsibility, cultivation, blessing. Freedom is not only waking up; it is living forward with purpose once awake.

Each morning, before emails, before conversations, before Zoom meetings…before it all; I stand at the sink and wash and I lift. It is a simple act. Water over skin. My hands raised in gratitude; not for what has already happened, but for what the day may bring.

Such a small ritual. Such a quiet moment at the mountain.

All because of Joan’s simple request: “Would you wash your hands?”

Her handwritten note beside the sink.

A small lift.

My spiritual springboard into the day.

Hands rise from the sink

Sleep loosens its narrow hold

A quiet Sinai

Appendix: The Morning Blessing for the Lifting of the Hands

The blessing recited upon waking and washing the hands:

Hebrew

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם

אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְּמִצְוֹתָיו

וְצִוָּנוּ עַל נְטִילַת יָדָיִם

Transliteration

Baruch Atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech ha-olam,

asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav,

v’tzivanu al netilat yadayim.

Translation

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe,

who has sanctified us with His commandments

and commanded us concerning the lifting of the hands.

Further Reading

If the themes of hands, freedom, and spiritual posture resonate, you may enjoy these related reflections:

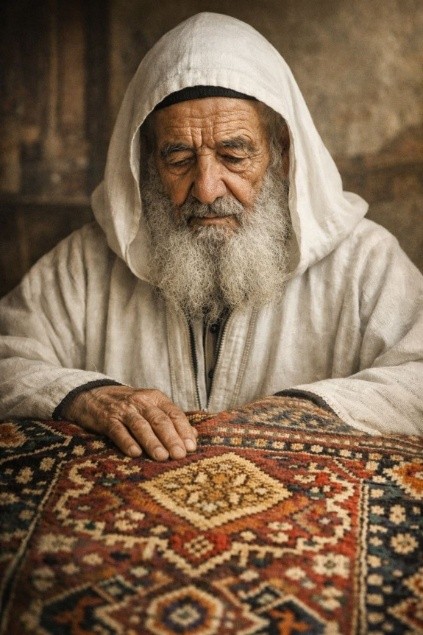

The Magic Carpet Was Never About Flying

A reflection on Joan’s family, the Baba Sali, and the deeper meaning of faith, merit, and responsibility within Jewish tradition.

An exploration of the Exodus through food. How slavery, wilderness, and the Promised Land are revealed not only in geography, but in what the Children of Israel ate, remembered, and imagined.