- According to tradition, Hanukkah, or the “Festival of Dedication,” celebrates the re-dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem after its defilement by the Syrian Greeks in 164 BCE.

- The holiday is also known as the “Festival of Lights.” Hanukkah usually takes place in December, during the winter solstice, a period when the days are shortest and darkest in the northern hemisphere.

- The number 25 matters, the name can be broken down into ה”כ ונח, “They rested on the twenty-fifth,” referring to the tradition that the Maccabees ceased fighting on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev and restored the Temple.

- Hanukkah is also called a “Second Succoth” because the Maccabees were away at war during the fall harvest festival and could not celebrate the Succoth holiday in its proper time.

- The term “hanukkat ha’bait” means “dedication of the home,” referring to the Jewish tradition of dedicating a new space by affixing a mezuzah (a small piece of wrapped parchment with verses from the Torah) to one’s doorpost.

Further Reading:

-הכונח (Hanukkah) can also be read as the acronym for: ללה תיבכ הכלהו תורנ ח, “Eight candles, and the law is like the House of Hillel.”

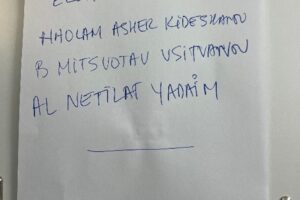

This is a reference to a famous disagreement between two ancient rabbinic academies—the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai—about how to properly light the Menorah: to count down or to count up? According to Shammai, eight candles should be lit on the first night, seven on the second night, and so on down to one on the last night (because the miracle was greatest on the first day). Hillel, on the other hand, argued that we should start with one candle and light an additional one every night, up to eight on the eighth night (because the miracle grew in greatness each day). The rabbis of the Talmud adopted the position of Hillel.

“Our rabbis taught the rule of Hanukkah: … On the first day, one [candle] is lit and thereafter they are progressively increased … [because] we increase in sanctity but do not reduce.”

– Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 21b

The earliest sources for the story of Hanukkah are the First and Second Maccabees, which describe in detail the Maccabean revolt and the rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem. These books are not part of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible); they are called Jewish Apocryphal books.

Later, Flavius Josephus (first century CE) wrote about Hanukkah in his historical accounts. Josephus connected the story of the military victory with the symbol of light, and the holiday still is often referred to as the “Festival of Lights,” following his terminology.

Multiple references to Hanukkah are also made in the Talmud. The story of the miraculous jug of oil lasting eight days is first described in the tractate of Shabbat (page 21b), first committed to writing about 600 years after the events described in the books of Maccabees. Interestingly, only a few sentences of text are devoted to the story of Hanukkah while there is a much longer discussion of when, where, and how to light the Hanukkah candles.

Throughout Jewish history, rabbinic commentators have interpreted the story of Hanukkah in multiple ways, with some emphasizing the underdog military victory of the Maccabees, while others focused instead on the miracle of the oil. In the Jewish mystical tradition there are many reflections on the symbol of light and the need to search out God’s holy light in all of life—including the darker parts of existence.