Do the clothes make the person? Can religious objects help us experience the sacred?

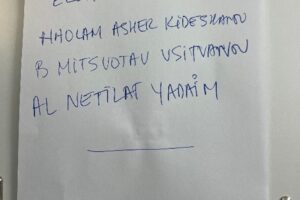

The tallit (or tallis) is a four-cornered prayer shawl worn by Jewish adults for various prayer services and other sacred occasions. In each of the four corners of the garment are strings wound and knotted in a special manner, called tzitzit. The tradition of attaching strings or fringes to one’s garment goes all the way back to the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible). The ancient instruction is to attach tzitzit to the corners of one’s garment as a way of remembering God and the commandments (Numbers 15:39). Therefore, many observant Jews wear a lighter version of the prayer shawl (called a “small tallit” or simply tzitzit) every day under or over their clothing as a way of reminding themselves of their beliefs and commitments. Traditionally, boys begin wearing tzitzit as early as age three. There are different traditions regarding the life stage at which a Jewish adult begins wearing a tallit. In many Jewish communities, it is first worn at bar/bat mitzvah age, while in others at the time of marriage. The tallit can be of any color or size based on custom and preference. We recommend purchasing one that is large enough to wrap yourself (or the bar/bat mitzvah) in as it can help create a sense of being enveloped in holiness. As Rabbi Goldie Milgram writes, “The tallit is a portable spiritual home.” In fact, the traditional blessing before donning a prayer shawl includes the words “to enwrap ourselves in the tzitzit.” The collar or upper band of the tallit is called the atarah (“crown”) and sometimes includes the blessing on it. The tallit is often kept in a special bag that comes with it.

The tallis and tallit bag Andy received for his Bar Mitzvah, March 21, 1981.

Max Fish’s (Andy’s great grandfather) tallit bags circa 1921.

Tefillin are leather prayer boxes worn by observant Jews (often beginning at bar/bat mitzvah age) on weekdays for the morning service (or longer). One box (known as the shel yad, “hand”) is placed over the biceps and wound around the arm, hand, and fingers. The second box (known as shel rosh, “head”) is worn on the forehead at the hairline with its straps going around the back of the head, and hanging over the shoulders. Inside each of the boxes are hand-written copies (carefully prepared by a trained scribe) of the four biblical texts that first mention the need to place signs of devotion to God on the arm and head. These include: Exodus 13:1-10, 13:11-16 and Deuteronomy 6:4-9, 11:13-21; the latter two are part of the famous prayer, the Sh’ma. While it is unclear exactly what it meant to place such markers on one’s body in the biblical context, the rabbis engaged in detailed interpretive discussions about these objects and their ritual usage over many centuries. For example, Rabbi Joseph Caro (16th century) explained that tefillin are placed on the arm, adjacent to the heart, and on the head, near the brain, to demonstrate that these two central organs are required to serve God fully. There is a moving teaching in the Talmud (Tractate Berakhot 6a) that just as Jewish worshippers wear tefillin, God wears a pair of tefillin on which is written God’s love for the Jewish people.

A special thank you to Rabbi Or Rose for his work on this article.