by Eswar Priyadarshan

Minyan

Our phones told us we were within 50 feet of the synagogue, but we could not find it. It was a busy street, with shops and restaurants open in the middle of the day, but no synagogue. Google Maps had pictures of a darkened passageway as a helpful hint, so we switched modes and walked back and forth, looking for a dark passage rather than a door or a sign. We finally found an awning and a passage similar to the picture and walked in.

Google Maps photograph of the Yad Lezikaron Synagogue in Thessaloniki (Salonica) – the dark passageway entrance is to the left of the awning.

There was a phone booth to the right, with someone seated in it as though it was their permanent daytime spot. A door to the left, with a sign in Greek that had the word “Thessaloniki” in Cyrillic and the word “NAZI” in English. We peered around, ready to withdraw given the sign, but then the door opened and a young bearded man in a dark suit and hat walked out. He looked at my wife and I and said “Hello” in Hebrew. My wife said “Hello” right back and asked if this was the synagogue and if he was the Rabbi. Yes, to both. She asked if or when we could come back for services because we needed to say kaddish. “4 PM,” he said, and left out onto the busy street.

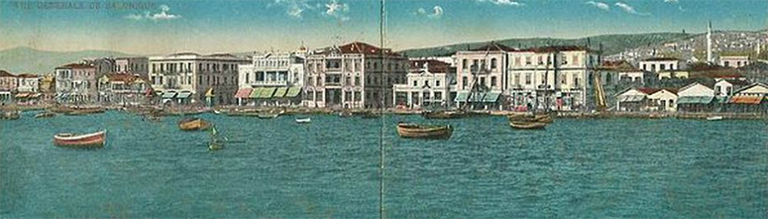

We wandered around downtown Thessaloniki, the city in Greece that used to be called Salonica in its Jewish heyday. It has its own ancient Hagia Sophia church, as old as Christianity itself, with the colors and architecture of Greek Orthodoxy within and crazy graffiti spray painted without. The church began as a Byzantine monument, was converted to a mosque and then back to a church again.

The old church turned mosque turned church.

There’s a waterfront promenade along the Aegean Sea, with water as dirty as Boston Harbor in its toxic prime. And there’s a stone tower, the favorite lock-em-up spot for whomever ruled the city in whatever era – archaic, Hellenic, Byzantine, Roman, Crusader and Ottoman.

The White Tower along the waterfront.

We returned at 4pm. There was now another bearded guy up front at the door. He was your basic Israeli badass – requesting our names and passports, asking why were we in town and why we were visiting the synagogue, opening our bags and taking everything out – no please or thank you, just a very serious focus on making sure we meant no harm. We passed inspection and walked in the door.

There was a large map on the wall indicating the 57 synagogues of Salonica. There are only 2 remaining – the one we stood in and one other, which opens only during the High Holy Days. My wife first went upstairs and was quickly shooed back down to a small curtained partition on the ground floor. I sat in the main area with two other men and we waited for a minyan. Men and women trickled in – the men were mostly in their 60s on up. We continued to wait – I wondered if they would count me in the minyan count of 10 men.

The interior of the Yad Lezikaron synagogue.

I marveled at the beauty of the interior, especially relative to the busy, average street and the nondescript passageway leading to a room next to a phone booth.

We reached 10, including me, and we still waited. It was clear that the definition of 10 in this group meant 10 people known to one another. Eventually, one more man walked in and the oldest of the groups began the program. The Rabbi eventually arrived around 4:45pm and took control.

He stopped abruptly, looked at me and asked if I/we still wanted to say kaddish. “My wife”, I started to say. “Only men”, he said.

I was on alert. My wife seemed to be in deep conversation with one of the ladies – I wondered if it was in English, Hebrew or rudimentary Greek since she (my wife) has the uncanny ability to scoop up languages on the fly.

The service continued. The Rabbi stopped again.

“Now?”, he said to me. “For my wife’s mother…”, I began to say. “Only men now”, he said. I have been attending Jewish services for 20 years yet I realized how little I knew of things a Jew would know naturally.

Finally, another, “Now”, from the rabbi. I said my wife’s mother’s name, “Sandra Kass”.

“Katz?”, he said. “No, Kass”, I said. He looked puzzled because Katz fit perfectly and Kass was probably another one of my stumbles.

A man behind me snorted and started to walk out at this back and forth. My obvious ignorance and the Rabbi accommodating me had really offended him. The Rabbi stopped and lectured the man in Greek, probably about the importance of treating a stranger as one of your own. The offended one returned to his seat.

The gentleman seated closest to me came over with his book and walked me through the Kaddish line-by-line – I was very moved by his gesture. I was briefly a member of this small community, embraced and participating despite my awkwardness. I was touched by a universal grace.

Memory

Thessaloniki is an old city in Macedonia. It was founded in 315 BCE by Cassandra of Macedonia, who named the city for his wife Thessalonica, the half-sister of Alexander the Great. It has seen every kind of movement toward civilization and backslide towards catastrophe that you can imagine (including a great fire that destroyed most of the city in 1917). It’s a poor city in a poor country, made poorer and more on the edge by being a gateway from the Balkans to Europe. While you notice an absence of young people in Europe in general, you really notice the absence in Thessaloniki.

The first Jewish refugees in Salonica arrived from Palestine and Alexandria from 145-135 BCE. The Jewish community grew over the centuries and was by no means homogenous. The Greek Jews drew their traditions from the Palestinian Talmud while the European Jews drew from the Babylonian. They spoke Greek, Yiddish, Italian and finally Spanish from a massive influx of Sephardi expelled from Spain at time Columbus set sail for the New World.

A Nazi officer humiliates Jews in Salonica’s Freedom Square.

Salonica had the largest Jewish population in Europe at one point. Close to 50,000 Jews lived in the city as of July 9, 1942. Two days later, there were virtually zero., The Nazis had rounded up all of the Jews, humiliated them in public and sent them from the train station to the concentration camps.

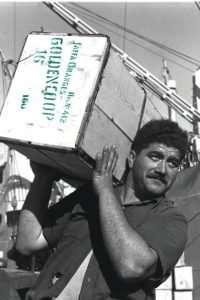

Salonica was aflame with Zionist zeal during the early 20th century. Zionism wasn’t just for the intellectuals, the idea cut across all sectors of Jewish society. Tel Aviv port was built by Jewish dock workers from Salonica. Fifteen landed from Salonica in the summer of 1933. A Zionist, socialist commentator saw them at work a month later and was amazed – they were the brawny, Jewish epitome of the Zionist dream.

“The Jews here spend their lives doing things even the Arabs can’t do back home. I stood on the docks and watched the ships being unloaded just as you’d told me. I spoke to the workers carrying the coal, and they were as blackened by it as the Egyptians from Port Said who work in Haifa. But the Thessalonikans are better workers.”

Isaac Molho, Thessalonikan Mariners in Israel – Vision and Fulfillment, p. 58 [Hebrew]

A Salonican hauling oranges in Haifa Port, 1948.

Fast forward to today. You have to dig deep and do your own research to find evidence of the Jewish history in the city. There’s the small Jewish memorial museum and one other monument – a sculpture created in a local parking lot along the water in the early 2000s. The sculpture has been cordoned off from the main parking lot with some bushes since then.

The 21st century memorial to the Jews of Salonica near a waterfront parking lot – it has faced a rash of anti-Semitic vandalization this past summer.

The Jewish museum has a wall of the names of those citizens killed in the Holocaust. My wife’s stepfather was an Eskenazi originally from Salonica – there were many Eskenazis on the wall. My wife stopped, shocked and too moved to continue at one point, when she saw other family names – names of her stepfather’s family friends also from the old country. Here we were, ostensibly strangers in a new city in a new country, confronted with kinship and friendship from generations past.

I thought about the long, difficult history of the city, about the sign outside, the names on the museum wall, the Holocaust memorial in a parking lot, the map of the other synagogues now forever gone, our serious interrogation by the security guy and the time and effort it must be for the few remaining, committed Jews in town to somehow make a minyan on a weekday afternoon.

I thought about what it means to remember and the vital need to remember. I thought about rituals like saying kaddish and of people staying with their traditions despite violent suppression or just plain indifference. I thought about the busy street where we struggled to find the synagogue and how the minyan and the service seemed like a dream when we stepped back out into the street. The future is history, says a recent book title, or is it history that is the future, as the chaos of Brexit, the chaos in France or our own political upheaval seems to be telling us?

How do we keep from joining the indifferent? We can’t control the future but we can so easily choose to forget the past. The only way, it seems, to re-connect our everyday lives with the past we must honor and cherish, is to walk off the busy street, through the darkened passageway and gather and recount the names and the journeys with anyone of good faith who will join us.

Eswar Priyadarshan and his wife Jill Eskenazi are Boston transplants currently living in the Bay Area. Theirs is a Jewish, Hindu, Christian and atheist household where everyone is expected to remember. Their kids Sunjay, William and Sarah are very fortunate to have grown up with their grandmothers Dorothy Downing, Sandra Kass and Saraswathi Singh as a constant and reassuring presence.

Eswar and Jill were recently in Thessaloniki to visit their daughter Sarah, who was in a semester-abroad program at Northeastern University.