Food of the Exodus

Freedom has a taste. Not a single taste, but a progression. Each stage of liberation is marked by what the Children of Israel ate, what they remembered, and what they imagined. The Exodus story can be traced through food, because food reveals orientation: whether the Children of Israel look backward toward familiarity, experience an initial moment of freedom, or look forward toward possibility and responsibility.

Food of Slavery

Despite reaching freedom by escaping Egypt, the Children of Israel complained bitterly in the wilderness. One of their central complaints was about the discomfort of the present, expressed through longing for the food of the past. They spoke of garlic, leeks, and onions pulled from the ground. All rooted foods from the adama. They remembered what was familiar while overlooking the suffering that defined their bondage, clinging to the false comfort of what they once knew.

The complaint was not really about taste; it was about fear. Slavery, at least, felt known. Even a painful past can feel more familiar, and therefore safer than a future that demands change.

The Torah exposes a difficult human truth: the Children of Israel often complained about the present by romanticizing what once enslaved them. Memory becomes a refuge from uncertainty, even when that memory distorts the truth.

Food of the Wilderness

The wilderness introduced an entirely new relationship with food. Manna did not come from the ground and did not grow on trees. It fell from the sky—daily, exact, and sufficient. It could not be stored. It could not be controlled. Manna forced a newly freed Children of Israel to experience freedom of the present.

Manna was not only nourishment; it was education. It trained the Children of Israel to gather enough and then stop. To live without hoarding, to trust tomorrow’s portion, and to learn what enough truly means.

With manna came the first Shabbat. For the first time, sacred time entered Israel’s life through food. A double portion fell before Shabbat and gathering was forbidden on the day itself. The lesson was radical: survival did not require constant labor. Freedom was marked not by movement, but by restraint and trust.

We continue to celebrate the lessons of the wilderness today. The double portion lives on each week in the two challahs placed on the Shabbat table. They are not decoration; they remind us to pause, to prepare, and to trust.

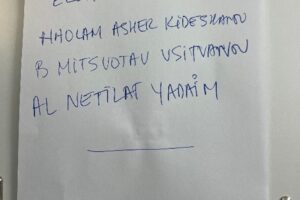

Blessings reinforce this education. Some foods come from the ground and others from trees, each requiring a different blessing. This practice is explored more fully in Savor the Celebration. Even before interpretation, the act of blessing teaches orientation: earth below (adama), growth above (ha’etz), and beyond both (shehakol), a Source not fully seen. Manna, belonging to neither soil nor branch, completed the lesson. Not all sustenance is earned the same way. Not all freedom is built on control.

Food of the Promised Land

When the twelve spies entered the Promised Land, they did not return remembering what once was. They returned carrying fruit: grapes, figs, and pomegranates declaring: “This is its fruit.” Their language was not nostalgic; it was demonstrative. Not memory, but evidence.

The contrast is deliberate. The Children of Israel remembered slavery in Egypt, using the past to protest the hardship of the present. The twelve spies spoke of the land by pointing forward, holding in their hands proof of what could grow. The food of the Promised Land was not about immediate consumption, but about future cultivation. Trees that bear fruit, seeds that regenerate, and abundance that unfolds over time.

Another way to see this progression is through how we use our hands to eat. Animals eat with their mouths lowered to the ground. The food of slavery—garlic and leeks—were taken in much the same way, with hands reaching downward into the earth.

In the wilderness, the posture of the hands changed. Manna was gathered from the sky and carried with care, training the hands to move between levels. Reaching downward to gather, held at the center with intention, and lifted upward toward the heavens in faith.

In the Promised Land, food comes from trees—figs, olives, and pomegranates—requiring the hands to reach upward, almost in a posture of praise. When the hands return to the earth, it is no longer to clutch, but to plant. To place seeds gently into the ground for future growth.

The Torah’s food story reveals a lasting struggle: leaving slavery is easier than leaving the mindset it creates. Complaining about the present often disguises itself as longing for the past. True freedom begins when desire itself is retrained. When memory no longer anchors us backward and faith allows us to move forward.

When the Children of Israel looked backward, they complained about the present and idealized the food of slavery; when the spies looked forward, they carried fruit from the land.

Every Shabbat, when two challahs rest on the table, the journey is quietly reenacted. We remember the ground, the sky, and the trees. We bless what sustained us, what grows among us, and what we cannot control. We remind ourselves that liberation is not only escape from what was, but the courage to believe in what can still grow.

Slavery fed memory, the wilderness taught faith, and the Promised Land invites the Children of Israel to plant, tend, and believe in a future that will grow.

Hands once reached downward

Then lifted, learning to trust

Now they plant and bless

Appendix: Torah Sources on Food, Memory, and Freedom

- Food of Slavery — Mitzrayim (“Narrow Place”)

In Egypt, the Israelites ate foods later remembered as the food of slavery, all described as coming from the ground and associated with familiarity and predictability.

- Numbers 11:4–5 (JPS, p. 307)

“The riffraff in their midst felt a gluttonous craving… We remember the fish that we used to eat free in Egypt—the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic.”

- Food of the Wilderness — Midbar

The wilderness introduces an entirely new form of sustenance: manna, food that comes neither from soil nor from trees, but directly from heaven. It is given daily, cannot be hoarded, and is paired with the first experience of Shabbat.

Manna

- Exodus 16:15–16 (JPS, p. 148)

“When the layer of dew lifted, there on the surface of the wilderness lay a fine and flaky substance… Moses said to them, ‘That is the bread which the Lord has given you to eat.’ … The House of Israel named it manna.”

Shabbat and the Double Portion

- Exodus 16:26 (JPS, p. 149)

“Eat it today, for today is a Sabbath of the Lord; you will not find it today on the plain. Six days you shall gather it; on the seventh day, the Sabbath, there will be none.”

Spiritual Framing

- Deuteronomy 8:2–3 (JPS, p. 393)

“God subjected you to the hardship of hunger and then gave you manna to eat… in order to teach you that man does not live on bread alone, but that man may live on anything that the Lord decrees.”

III. Food of Freedom — Eretz Zavat Chalav U’Dvash (Promised Land)

The Promised Land is consistently described through abundance, sweetness, and cultivation. Its food grows from trees and fields, requiring time, patience, and partnership with the land.

Divine Promise

- Exodus 3:8 (JPS, p. 116)

“I will rescue them from the Egyptians and bring them… to a land flowing with milk and honey.”

Report of the Spies

- Numbers 13:23 (JPS, p. 312)

“They reached the wadi Eshcol, and there they cut down a branch with a single cluster of grapes… and some pomegranates and figs.”

Vision of Abundance and Gratitude

- Deuteronomy 8:7–10 (JPS, p. 393)

“For the Lord your God is bringing you into a good land… a land of figs and pomegranates, a land of olive trees and honey… When you have eaten your fill, give thanks to the Lord your God for the good land which He has given you.”