Last Sunday, I smiled when I ruptured my Achilles tendon playing padel. Twenty years earlier, I broke my racquet in anger while competing for a tennis club championship. That break was intentional. This one was not.

Back then, when I competed in tennis and squash championships, winning was everything. Nothing else mattered. Now, humbled by a life of learning, three Achilles ruptures, and two hip replacements, I play for camaraderie, not competition. Playing the game matters more than winning it.

When I re-ruptured my Achilles for the fourth time, balancing briefly on my good leg before collapsing onto the court, I immediately recognized the pain and understood the implications. A birthday dinner in Boston with my daughters the next day became impossible. A long-anticipated four-week trip to the UAE, Israel, and Bahrain, planned carefully over months, vanished in an instant. Lying on the court waiting for the ambulance, I smiled.

Some people were surprised by my photo. “Only you could still smile in circumstances like this,” they said. I smiled because I recognized the moment. Not just the pain, but the terrain.

I kept returning to a Japanese proverb: 七転び八起き (nanakorobi yaoki)fall seven times, stand up eight. With this now being my sixth operation on my legs, I am getting close to this being literal, not just metaphorical. At face value it sounds like resilience, but its deeper wisdom is acceptance rather than defiance. The proverb does not celebrate the fall or dramatize recovery. It assumes falling is inevitable. What matters is your posture afterward, rising without self-doubt or anger. Standing up again was never really a question of if, only how.

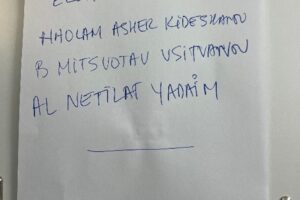

There is a line in Proverbs that echoes the same quiet truth:

כִּי שֶׁבַע יִפּוֹל צַדִּיק וְקָם

Ki sheva yipol tzaddik ve-kam

For the righteous person falls seven times, and rises again.

The verse does not praise the fall, nor dramatize the rise. It assumes both. Falling is not a failure of righteousness; it is part of it.

The Torah understands this posture well.

Moses is its most nuanced case study. His leadership begins with rage: seeing an Egyptian beating a Hebrew slave, Moses intervenes violently. The act forces him into exile, yet also draws an uncompromising moral line. Oppression cannot be tolerated. Later, descending from Sinai, Moses sees the Golden Calf and shatters the Tablets. Something sacred is broken in anger, yet that rupture clears the way for repentance, forgiveness, and the second Tablets, which endure. When Moses later strikes the rock instead of speaking to it, his anger costs him entry into the Promised Land. The same temper that once advanced redemption now halts it.

Jonah presents the opposite failure. Jonah is not angry at injustice, but at mercy. When God spares Nineveh, Jonah burns with anger. His temper narrows rather than enlarges his moral vision. God’s final lesson is devastatingly gentle: if Jonah can grieve a plant that shaded him for a day, how can he begrudge compassion to an entire city? Jonah’s anger is stirred by mercy he did not expect.

David offers a third path. When the prophet Nathan tells David a parable of a rich man stealing a poor man’s lamb, David erupts in righteous fury. Nathan’s reply: “You are the man” turns that anger inward. David’s greatness lies not in avoiding temper, but in yielding to truth once revealed. His anger becomes the catalyst for repentance rather than denial.

A modern parallel sharpens the insight. John McEnroe famously played better tennis when he was angry. His outbursts were not incidental; they activated focus. Rage pulled him fully into the moment and unlocked elite performance. For McEnroe, anger functioned like Moses breaking the Tablets: disruptive, even ugly, yet sometimes catalytic.

By contrast, his legendary rival Björn Borg embodied restraint. Ice-calm and silent, Borg achieved extraordinary tennis dominance through emotional control and consistency. Yet even this ideal carried a cost. Borg burned out early, leaving the sport at twenty-six. Perfect containment proved powerful, but not indefinitely sustainable.

The Torah leaves us with an uncomfortable truth: Tov erech apayim migibor: better one slow to anger than a mighty warrior. The goal is not to erase emotion, nor to glorify it, but to master it. Anger that breaks idols may be necessary. Anger that resists growth is destructive. Restraint that preserves dignity is powerful, but restraint without integration can exhaust the soul.

Some things, like tablets, can be broken and renewed. Others, once struck, cannot be entered again. Lying on the court, smiling through the searing pain, I understood the difference.

Fallen on the court

I know this ground by heart now

Standing will come—with a smile

Appendix:

Andy playing tennis with John McEnroe at a charity event in Boston, wearing Björn Borg underwear. Predictably, McEnroe got mad when he noticed. Then—older, mellower—he smiled for the photo.

If this reflection resonates, it continues in a different form in my TED-style talk, “How Nothing Is What Matters the Most.”

Appendix: Torah & Textual Sources Referenced

Moses

- Moses kills the Egyptian taskmaster and flees into exile: Exodus 2:11–15

- Moses descends from Sinai and breaks the Tablets after the sin of the Golden Calf: Exodus 32:19

- The second Tablets are given after repentance and forgiveness: Exodus 34:1–29

- Moses strikes the rock instead of speaking to it and is barred from entering the Land: Numbers 20:7–12

Jonah

- Jonah reacts angrily when Nineveh is spared: Jonah 4:1

- The episode of the plant (kikayon) and God’s lesson on compassion: Jonah 4:6–11

David

- Nathan’s parable of the rich man and the poor man’s lamb: II Samuel 12:1–7

- David’s immediate recognition and repentance: II Samuel 12:13

Proverbs

- “Better one slow to anger than a mighty warrior”:

Proverbs 16:32

Tov erech apayim migibor - “For the righteous person falls seven times, and rises again”:

Proverbs 24:16

Ki sheva yipol tzaddik ve-kam