On July 19th, I attended Shabbat services at the brand-new Chabad of Lenox, Massachusetts. It opened the prior weekend and this was their second Shabbat service. When I introduced myself to Rabbi Levi Volovik, I mentioned that I am a “Kohen.” I have recently learned the importance of being a Kohen and the critical role of serving the first Aliyah.

As fate would have it, when they began the Torah reading, they needed me as the Kohen for the first Aliyah. I was stunned and moved that the portion was Numbers 26, where Moses commands Eleazar to take a census of the Children of Israel. It was the second counting of the Jews after leaving Egypt. As I read along with the Rabbi, I noticed that the word “Kohen was mentioned in the very first sentence of the parsha which was my Aliyah. This was no coincidence, it was spiritual choreography.

When I reflected on the Torah portion and my role as the first Aliyah, I was drawn to the meaning of math in Jewish tradition.

I remember the first time I helped make a minyan. I was living in Miami, relaxing in the hot tub before Shabbat. A neighbor approached me and said, “I remember meeting you, you’re Jewish.”

“I still am,” I replied with a smile, “and intend to be.”

He asked if I could be the tenth man for a minyan in the building. I said yes but needed to go up and change. “We need you now,” he said.

I hurried upstairs and asked my life partner Joan if it would be alright if I was late for our Shabbat dinner. “Making a minyan is a great mitzvah,” she said. “Take your time.” I heard her words and felt her blessing, but I still didn’t fully understand their depth.

It turns out that Adam (we later became friends) had invited his father-in-law, Howard, who was mourning the loss of his father, Menachem (of blessed memory (Z”L) )They needed a minyan so he could say Kaddish. My presence, as the tenth member, gave voice to his mourning. Later, at Shabbat dinner, Adam’s wife, Dana, thanked me. Her father had found comfort because he was able to say Kaddish for her grandfather (his father), surrounded by others.

I once believed that prayer was a private conversation with God: intimate, internal, solitary. Leaving that hot tub to make a minyan for a mourner forever changed my understanding. I didn’t know the mourner nor the full prayer. I showed up out of a feeling of obligation. In showing up, I discovered that presence itself is a form of prayer. That sometimes, being the tenth person is more important than being the first.

A minyan (ten adult Jews gathered for communal prayer) is not just a rule, it’s a sacred structure. Certain prayers, like Kaddish or the Barchu, cannot be recited alone. It’s not because God isn’t listening. It’s because some holiness only emerges in community.

This is not a modern invention. It’s rooted in Torah.

In Numbers 26, God commands Moses and Eleazar, son of Aaron, the Kohen to conduct a census of the Children of Israel, tribe by tribe. This was not the first census, the earlier generation had been counted in Numbers 1, with Aaron himself beside Moses. This second census marked a spiritual threshold: the old generation had passed; the new stood on the edge of the Promised Land. Each person was counted not just to tally totals, but to affirm identity, purpose, and place.

Counting, in the Torah, is singularly sacred. Every number reflects a soul. Every soul reflects a spark of the divine. What Rebbe Nachman of Breslov called nitzotzot, holy sparks hidden even in brokenness, waiting to be lifted through prayer, mitzvot, and joy.

There are reasons why ten is the number of a minyan. Ten is a number of completeness in the Torah:

– Ten utterances of creation (Genesis 1)

– Ten trials of Abraham (Pirkei Avot 5:3)

– Ten commandments (Exodus 20)

– Ten fingers on the tombstone of a Kohenim

Ten isn’t an arbitrary value, it’s a deliberate structural choice. Like a skeleton supports the body, ten supports sacred community.

My friends Michael and Tasja once taught me about the intricate organization of a bee colony. Each bee has a distinct role—worker, drone, queen. Yet no one commands them. Their service arises through ritual rhythm. Through inherited instinct. The hive is not just a place of production; it’s a choreographed community. Bees create harmony in their hierarchy.

The minyan is our hive. When we show up, we join a sacred prayer not just with our voices, but with our presence, and holy hum. The prayer may be led by one, but it lives in the ten. Especially when the mourner rises to say Kaddish, and we rise too in sacred solidarity.

Then there’s the role I played, not just as one of ten, but as a Kohen, a descendant of Aaron.

I used to wonder what it meant to be a Kohen. Was it just a title? A relic, remnant or ritual of Temple history? But then I began to understand: Being a Kohen is not the coda but the beginning of the blessing. The Kohen are not the center, but the catalyst for consecration of a compassionate community.

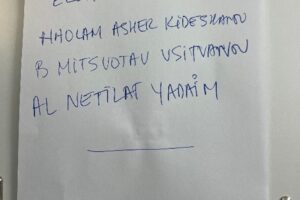

In Numbers 6:22–27, God instructs Moses to teach Aaron and his sons the priestly (Kohenim) blessing—“May the Lord bless you and keep you…” These words are not magic. They’re spiritual fermentation. When a Kohen lifts his hands to bless, he doesn’t impart holiness. He activates it. Like yeast added to flour and water, the blessing causes the sacred to rise.

Being a Kohen is like being a sourdough mother starter. It’s not the loaf, but it helps the loaf come to life.

When I worked for the founding family of Kikkoman Soy Sauce in Tokyo, I learned how, after World War II, Kikkoman shared its fermentation agent with other manufacturers to help rebuild. Working at the Goyogura factory which is dedicated to the Emperor of Japan, I learned the process began with cultivating a Koji mash to start fermentation.

Like koji mold in soy sauce—transforming beans into something richer, deeper, more enduring.

Later, I bicycled through Tuscany and met a family who had been making Vin Santo, an Italian dessert wine, for over a century. I learned about their wild yeast—the cherished mother starter—which had been nurtured and passed down through generations. This story was told by the patriarch of the family, who had recently lost his wife. As he spoke about the sacred continuity of the fermentation process, I sensed a momentary easing of his grief. His tears, born of sorrow, were reflected in our collective awe as we absorbed the depth of his story.

Even now, when I sip his wine, I taste more than sweetness. I remember his love, his mourning, and his oenological ode to family, memory, and time.

In that moment, I thought of the verse, “Wine gladdens the heart of man” (Psalms 104:15). Just as wine is sanctified in Kiddush to mark sacred time, his Vin Santo became a vessel of both zachor (to remember) and nichum (to comfort). Through the wine, his pain was fermented into a legacy, a living blessing passed forward like the yeast itself.

Like the wild yeast of Vin Santo, the Italian dessert wine slowly fermenting into sweetness over time.

Returning to the bees, one of their most vital attributes is their role in cross-pollinating flowers, fruits, and vegetables throughout the surrounding area. In doing so, bees act as natural catalysts of vitality, enhancing the health, growth, and abundance of plant life wherever they roam.

Like a bee, the Kohen cross pollinates across the Jewish Community. The Kohen is the fermentation agent—subtle, invisible, essential.

Maybe that’s why the minyan matters so much. Because it’s not just about having ten people. It’s about having ten catalysts, ten contributors, ten witnesses. When one person mourns, the other nine don’t just attend, they ferment comfort and activate remembrance.

I also reflected on the mesmerizing beauty of math. I thought about how families can find emotional connection through numbers. When my children were young, I remember teaching them math. I gave Caroline and Lucy each a Math Notebook, a pencil, and a big eraser. I explained the importance of always showing your work, of not being afraid to make mistakes, and of keeping a written log of their mathematical journey. The notebook wasn’t just for equations, it was a record of growth, persistence, and wonder.

Lucy and I also used to watch a television show called Touch, in which a nonverbal child named Jake communicates through numbers. He sees hidden connections between strangers across the world, threads of destiny revealed in math. His father, played by Kiefer Sutherland, seeks emotional connection with his son by joining Jake on numerological quests. Through numbers and formulas, they find meaning, connections, and ultimately love.

The show suggests what the Torah has whispered all along: numbers are not just tools of calculation they are vessels of creation. From the ten utterances of creation in Genesis, to the counting of the Israelites in Numbers, to the Ten Commandments at Sinai, the Torah teaches that numbers carry spiritual weight. They reveal order, purpose, and connection. Like Jake, and like my daughters learning math, we are invited to see numbers not as barriers, but as bridges linking mind to heart, and soul to soul.

When we gather ten for a minyan, we step into that design. Completing an equation first written in the wilderness. Echoing the census of Numbers 26. Participating in a pattern as old as Sinai.

I’ve come to believe there are two schools of communal math. One seeks division, subtraction, and fractions. It breaks people apart into tribes, egos, ideologies. It sees difference as a threat and connection as compromise. This is the math of Babel, where language divided rather than united (Genesis 11). It’s the rebellion of Korach (Numbers 16), who split the community with jealousy and pride and was ultimately subtracted from the earth itself. It’s the math of the Golden Calf (Exodus 32), where fear led to fragmentation, and Moses shattered the tablets literally breaking the divine covenant in two.

The Torah teaches a different kind of math—a sacred arithmetic of addition, multiplication, and even exponential blessing. God promises Abraham: “I will multiply your descendants like the stars of heaven and the sand on the seashore” (Genesis 22:17). This is not merely population—it is legacy. Depth. Endurance. Even in Egypt, under Pharaoh’s oppression, “the more they were afflicted, the more they multiplied and spread” (Exodus 1:12). This is exponential resilience. It is the spiritual logic of hope.

And during Chanukah, following the tradition of Beit Hillel, we light the Chanukiah with increasing candles—one more each night—until all eight flames glow in fullness. Light expands, not contracts. Blessings build. This is sacred math not of scarcity, but of abundance. The Torah’s math kindles a world where faith, joy, and presence are multiplied into radiance.

When we count souls in Torah like in Numbers 26, it’s not about headcount, it’s about hearts. The census doesn’t divide, it dignifies. When ten gather for a minyan, we don’t just add, we elevate. This is the school of math I want to belong to: the one where kindness multiplies, where blessings grow algorithmically, where the spiral of the Torah unrolls into infinite meaning. Like a fractal, the more we turn it, the more we see. In the language of Pirkei Avot (5:22): “Turn it and turn it again, for everything is in it.” This is not just math. This is sacred geometry.

So now, when someone asks, “Can you help make a minyan?” I see it not as an obligation, but an opportunity. I see the hive. I see the starter. I see the mourner waiting to speak the unspeakable and needing nine others to lift his voice heavenward. I see a sacred system, patterned and alive, where everyone counts and everyone helps others rise.

I show up. Not to be seen. But to activate the unseen. Because in this divine mathematics, being present is enough to make a blessing rise.

Enjoy a haiku inspired by this blog:

Silent hands are raised—

Ten sparks lift a mourner’s voice,

Blessings rise unseen.

Appendix

You can read more about the Kohen here.

You can read about the connection between the Kohen and the famous Vulcan salute here.

You can read more about Jewish mourning here.

You can read about the shehecheyanu blessing here.

You can read more about the brand-new Chabad of Lenox, MA here.