by Myra Outwater (of blessed memory), Judaica (1999)

Like most Jewish ceremonial items, the lulav (palm branch, myrtle, and willows) and the etrog (citron) have philosophical meanings. The ancient rabbis spent many hours discussing and trying to interpret the words and meanings of each law. And through the centuries, they have handed down various interpretations of the symbolism of the lulav and the etrog.

One popular rabbinic teaching is that the four components of the lulav and the etrog, which are called in Hebrew the arba minim, symbolize the human condition and one’s relationship with God. The etrog is shaped like the heart, and the lulav like the spine. The myrtle leaves are shaped like the eyes, and the willow leaves like the lips. Together, these four elements show that one should serve God with his or her heart, spine or body, eyes and lips.

There is another symbolic layer of meaning related to the etrog and lulav and two forms of Jewish sacred action: study and good deeds. The etrog, which has a good taste and a good smell, is like those who know the Torah and do good deeds. While the lulav which has a good taste, but no smell, is like a person with knowledge, but who does no good deeds. The myrtle, which has a good smell and no taste, is like a simple person who has no knowledge and learning, but is innately kind and caring. Lowest on the rung of human values is the willow, which has neither taste nor fragrance, and symbolizes those people with no interest in gaining knowledge and no innate sense of responsibility towards others and no feeling of the need to help others.

Each day during Succot, blessings are recited over the etrog and the lulav. The etrog is held in the left hand the lulav in the right hand. Then the lulav is shaken in six directions (north, south, east, and west, up and down) to remind us that God is everywhere.

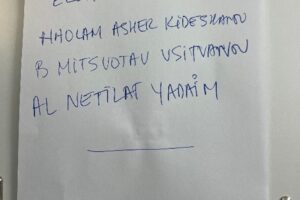

In order to protect and adorn the ceremonial objects used on Succot, there is a special box used to store the etrog and a case in which to carry the lulav. Since traditional Jews believe that an etrog must be as perfect as possible, the etrog is carried to services in an etrog box in which there is usually a cushion of soft material. Traditional etrog boxes are usually in the shape of the fruit itself. Early etrog boxes were adapted from silver sugar bowls, soap dishes and other silver containers. In the late 19th century many tourists brought back olivewood etrog boxes from the Holy Land. Today, most etrog containers are silver, pewter, ceramic, or olivewood. Many families allow the etrog to wither and save it in the etrog box, using it as a ritual spice during the weekly havdalah (“separation”) ceremony marking the end of the Sabbath. The lulav is usually carried to services in a lulav carrier made of plastic, wood or velvet, which includes the blessing over the etrog and lulav on or in it.