by Rabbi Or N. Rose

On a recent Saturday afternoon, I took the opportunity to re-read selections from Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel’s book, The Sabbath. First published in 1951, this poetic gem has been read by countless spiritual seekers — Jewish and non-Jewish — throughout the world.

As I flipped through the pages, I was struck again by Heschel’s remarkable ability to cull from the vast storehouse of classical Jewish teachings and to present these gleanings to a diverse modern readership with elegance and force.

In Heschel’s mind, the greatest challenge facing the modern Western world is the loss of a sense for the sacred. He argues that in our attempts to master our physical surroundings through technological advancement, we have become desensitized to the grandeur and beauty of life, both in the natural world and in the faces of other people. In our rush to industrialize we have become so focused on gaining economic and political power that we have forgotten our ultimate purpose: to serve as co-creators with the Divine in the establishment of a just and compassionate world.

For Heschel, a refugee from Eastern Europe, the Holocaust is the most dramatic example of the shadow side of modernity. After all, it was Germany — arguably the great center of modern cultures — in which one of the most effective and devastating killing machines in human history was created.

But Heschel is also critical of popular American culture with its seemingly insatiable consumerist cravings, symbolized in his mind by the excesses of affluent suburban life in cities across the country.

In The Sabbath, Heschel attempts to offer a corrective to this imbalance. In so doing, he explores two basic, and intersecting, dimensions of human existence: space and time. Heschel argues that modern Western life is dominated by an obsession with space — with building, mastering, and conquering things of space. But life turns dim, says Heschel, “when the control of space, the acquisition of things in space, becomes our sole concern” (p.ix). He calls on us to reconsider our priorities and relax our attachment to “thinghood,” shifting our attention to the “thingless and insubstantial” reality of time.

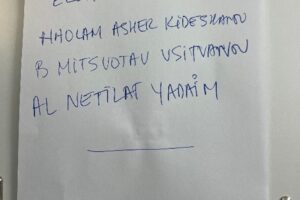

It is in this context that Heschel introduces the importance of the Sabbath to modern life. For Shabbat offers us the opportunity to retreat temporarily from our work-a-day routine, from the world of space consciousness, and to enjoy the manifold gifts of creation provided for us by the Master of the Universe. Heschel describes the Sabbath as a “palace in time,” whose architecture is built through a combination of intentional abstentions (e.g., refraining from business dealings, long-distance travel) and acts of prayer, study, joyous meals and interaction with loved ones.

Most importantly, perhaps, Heschel explains that Shabbat not only offers us an opportunity for weekly spiritual communion, but it also has the potential to help shape the way we live the other six days of the week.

Will our time with friends and family make us more sensitive to the needs of other human beings? Will our time celebrating the grandeur and beauty of nature make us more sensitive to the needs of the earth? Will we be able to hold in our hearts and minds the realization that God is the supreme author of life and that we are called upon by the Divine to serve as co-creators of a just and compassionate world? In brief, can we carry with us something of the Sabbath consciousness through the rest of the week?

More than sixty years after Abraham Joshua Heschel published The Sabbath, and thousands of years after this great religious institution was first recorded in the Hebrew Bible, Shabbat remains both a spiritual oasis and a bold challenge to all of us who seek to live both productive and reflective lives.