Before writing about Africa, I should start with why the stories of the Jewish journeys across Africa matters to me. I have a number of personal connections to journeys of freedom and faith that run through Africa. One of my dear friends’ father was directly involved in efforts that helped rescue thousands of Ethiopian Jews. Another close friend’s relative played a meaningful role in challenging and ultimately helping dismantle South Africa’s apartheid regime. My partner Joan’s family carries the legend of the Magic Carpet itself, rooted in Morocco and the Abuhazera tradition, offering not only rescue, but healing and continuity for Sephardic Jews across generations. These are not abstract histories to me. They are relationships. And it is through those relationships that Africa became, for me, not a place on a map, but a living chapter in the Jewish story.

People often ask about the Jewish connection to Africa, or the Israeli connection to Morocco, as if these were recent developments or strategic alliances. In truth, they are ancient relationships woven through exile and return, protection and peril, memory and miracle. They begin with a Torah command that predates borders and diplomacy: Lech lecha me’artzecha: go forth from your land, from what is familiar, before knowing where the journey will end (Genesis 12:1). In the Torah, movement comes before certainty.

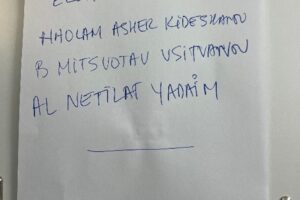

In my family, Africa is not an abstraction. It is carried in story. The “Magic Carpet” is not only folklore, but also the name given to an Israeli rescue mission.I It is also the family legend of the Abuhazera dynasty of Morocco, associated with Rabbi Yaakov Abuhatzeira in the nineteenth century. Passed quietly across generations, it was never about spectacle. It was a lived interpretation of Lech Lecha: ascent without guarantees, obedience before clarity, and trust enacted through motion.

Africa itself stood has long stood on the side of that kind of courage. In 1777, just one year after the American Declaration of Independence, Morocco became the first country to recognize the United States. Sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah made that decision with the counsel of his Jewish advisor, Samuel Sumbel. This move had risks to trade and diplomacy, defying the British Empire at a moment when convenience argued otherwise. It was an act that echoed a Torah mandate that appears again and again in Jewish history: lo ta’amod al dam re’echa—do not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor (Leviticus 19:16). History was moving, and Morocco chose not to remain still.

That same Torah spirit later animated Israel’s rescue missions across Africa. In late 1984 and early 1985, during Operation Moses, Ethiopian Jews made a perilous journey on foot from Ethiopia into Sudan. From there, in a covert series of flights, roughly 7,000 to 8,000 people were quietly brought to Israel. Their rescue was framed not by politics, but by prophecy. Jeremiah’s words: “I will bring them from the ends of the earth” (Jeremiah 31:8) ceased to be metaphor. Jews who had preserved their faith for centuries in isolation were suddenly free to practice it openly.

Seven years in May 1991, as Ethiopia descended into chaos, Israel launched Operation Solomon. In just thirty-six hours, thirty-five aircraft airlifted 14,325 Ethiopian Jews from Addis Ababa to Israel. One El Al 747 set a world aviation record by carrying well over 1,000 people—commonly cited at 1,088. With two babies reportedly born mid-flight, more souls arrived than departed. Rescue, quite literally, produced new life. My friend Charles’s father, Gene Ribakoff—who would have turned one hundred in 2026—was personally involved in that effort, a reminder that history often turns not only on governments, but on individuals who step forward when action becomes urgent.

I remember meeting members of the Ethiopian Jewish community in Haifa years later. Their stories of determination and earned distinction were profound. They carried Judaism not as theory, but as inheritance. Their traditions were biblical in origin, yet unfamiliar to many who assumed they already understood what Jewish life looked like. Like Abraham before them, they had gone forth without certainty. Like Jeremiah’s prophetic promise, they had been gathered from afar. They had come home not to be sheltered, but to serve. To stand in uniform, to contribute, and to assume responsibility for a future they had crossed continents to reach.

Before that journey came another. In 1949 and 1950, nearly fifty thousand Jews were airlifted from Yemen to Israel in what became known as Operation Magic Carpet. The Torah had promised, “I carried you on eagles’ wings and brought you to Me” (Exodus 19:4). For Yemenite Jews, that verse ceased to be poetry. The Jewish story in this region has never respected clean borders. Africa, Arabia, and Israel are overlapping verses in a single narrative of return.

Africa also produced moral leadership shaped by the same ethical imperatives. In South Africa, my dear friend’s great aunt, Helen Suzman, served in Parliament from 1953 to 1989, often as a solitary voice against apartheid. A Jewish woman challenging a system built on silence and cruelty, she lived the Torah commandment lo ta’amod al dam re’echa: do not stand idly by while your fellow’s blood is shed. When told her questions embarrassed her country, she replied that it was not the questions, but the answers that were shameful. She visited Nelson Mandela week after week during his long imprisonment, not because it was safe, but because moral responsibility rarely is.

Morocco occupies a singular place in this Torah-shaped story. During World War II, in 1942, the Vichy regime demanded lists of Jews living under Moroccan rule. King Mohammed V responded simply: there are no Jews here, only Moroccans. His refusal to participate in persecution was an act of pikuach nefesh: the protection of life above all else. For his resistance, he was later exiled by French authorities from 1953 to 1955. When he returned, the Moroccan people celebrated his reinstatement not as a political victory, but as a moral restoration.

In the decades that followed, Morocco’s Jewish population declined dramatically. Critics accused the monarchy of having “lost” its Jews. The King’s response: “I have gained global ambassadors” echoed a deeper truth of Jewish history: exile does not erase connection. To this day, Moroccan Jews return regularly, not as tourists, but as grateful descendants. I felt this most viscerally at a recent family wedding in Marrakech, when under the chuppah the rabbi and the bride’s father publicly thanked the King for allowing Jews to practice Judaism freely, without fear.

These bonds did not end with memory. They continue, quietly, in modern partnerships across Africa’s shores. What appears strategic today often rests on moral foundations laid long ago by those who answered the Torah’s call before knowing where it would lead.

The Jewish journey through Africa is not a footnote. It is a through-line written in Genesis, echoed by the Prophets, and lived across centuries: Lech Lecha—move before you know. “I will bring them from the ends of the earth.” Do not stand idly by.

The magic carpet it turns out, was never about flying. It was about Torah made real. About trusting the command to go and discovering, only in motion, that home was already waiting.