- How did it feel when you visited Israel for the first time?

- Have you ever been alone abroad but felt connected to your family?

After college graduation, I moved back to Japan. I had lived in Japan during high school and studied Japanese and Japanese history during college. I also worked for a Japanese company and developed a fluency in the language. I felt so comfortable and familiar in Japan. Although I was a Gaijin (foreigner), I felt at home.

Yet, as the Jewish holidays approached, I encountered an ancient ache: the dissonance between physical welcome and spiritual displacement.

I remember my first Rosh Hashanah at the Jewish Community Center in Tokyo. The melodies were familiar, but the voices were foreign. That dissonance stirred something deep within me. I was surrounded by others, yet alone in my yearning for home.

We hosted a Passover seder in our small apartment. Lacking brisket, we served kosher hot dogs. When we read the words, “In every generation, each person must see themselves as though they personally went out from Egypt” (Exodus 13:8), purpose was palpable in the air. We were distant from Jerusalem, but still drawn into its gravity through memory, ritual, and faith.

Years later, I stood in the desert of the UAE, praying beneath a boundless sky. Around me were Jews from Yemen, Morocco, Russia, and France. The siddurim were new, freshly printed, but the words were eternal. While we faced east, we felt Jerusalem.

These experiences have led me to reflect deeply on the meaning of the Promised Land, Exile, and Diaspora. Not just as historical events, but as living ideas that shape our spiritual geography. Why Israel is so fundamental to the existence of Jews and the meaning of Judaism?

Eretz Yisrael, our Promised Land, is not just a destination we travel to. It is our destiny, our reason for traveling and being, and our spiritual compass. Even when we are physically distant, Israel remains our heart that draws us inward and connects us outward. It is the thread that binds our past to our present purpose.

While we may live around the globe, our shared longing for return—whether literal or spiritual—transforms separation into unity. The Promised Land is what we carry in our prayers, our rituals, and our hearts. It is what makes us not just a scattered Children of Israel, but a determined Diaspora rooted in remembrance, and always reaching home.

From a biblical perspective, the Promised Land is explained in the following ways.

Promised Land in the Bible

God promises Abraham that he will make him a great nation and give his descendants the land of Canaan:

“To your offspring I will give this land.” (Genesis 12)

God tells Abraham, “Look up at the sky and count the stars—if indeed you can count them.” Then He said to him, “So shall your offspring be.” (Genesis 15:5)

Jacob recalls God’s promise, saying, “You said, ‘I will surely make you prosper and will make your descendants like the sand of the sea, which cannot be counted.’” (Genesis 32:12)

When Moses leads the Israelites out of Egyptian slavery, God promises to bring them to the Promised Land “flowing with milk and honey,” (Exodus 3:8)

G-d promised the Children of Israel = a place where they would always return and live with the blessings and fulfill the commandments set out at Mt Sinai and carried in the Mishkan.

“I will give you every place where you set your foot, as I promised Moses.” This passage marks the fulfillment of the promise made to the patriarchs, as the Israelites enter the land of Canaan. (Joshua 1:3)

God tells the Children of Israel, “For you are a people holy to the Lord your God. The Lord your God has chosen you out of all the peoples on the face of the earth to be his people, his treasured possession.” (Deuteronomy 7:6-8)

“Then the Lord your God will restore your fortunes and have compassion on you… He will gather you again from all the nations where He scattered you.” This passage reflects the hope of return from exile to the promised land. (Deuteronomy 30:3-5)

Living in the Promised Land of Israel

Living in the Land of Israel is considered one of the 613 mitzvot in the Torah. As it says, “When the Lord your God will cut off the nations… and you will inherit them, and you will dwell in their land” (Deuteronomy 12:29), and “You shall take possession of the land and settle in it, for I have given the land to you to possess” (Numbers 33:53).

The Talmud (Ketubot 110b) teaches that one should always strive to live in the Land of Israel, and that dwelling there is equal to fulfilling all the mitzvot of the Torah. This elevates the act of living in Israel; it’s not just a physical home, but a spiritual calling. Living in Israel becomes both a mitzvah and a way to draw closer to God.

Exile in the Bible

Jews have experienced exile multiple times. Perhaps the most significant exile in Jewish history is the Babylonian Exile, which followed the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem. The Jews were taken into captivity in Babylon (as described in books such as 2 Kings 25, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel). During this time, the Jews were separated from their land and the sacred city Jerusalem.

There was also the Assyrian Exile (722 BCE): The Northern Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Assyrians, leading to the exile of the ten lost tribes of Israel (as described in 2 Kings 17).

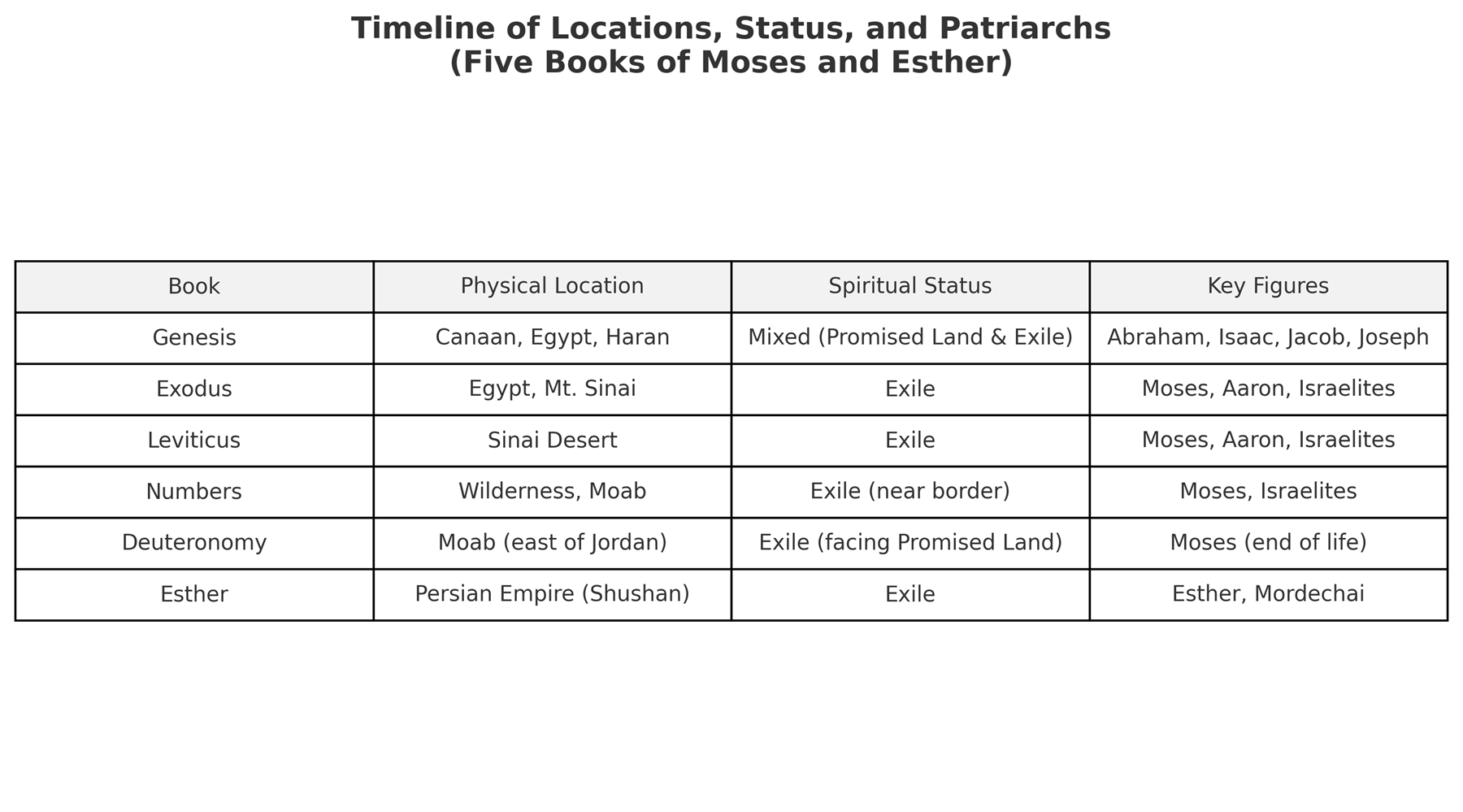

From Genesis to Deuteronomy, and into the scroll of Esther, we walk a sacred spiritual geography:

The patriarchs wandered. Abraham left Mesopotamia for Canaan, only to journey through Egypt. Isaac never left the Promised Land—rooted and steadfast. Jacob straddled borders and decades, his body returning to Canaan, his family descending into Egypt. Joseph rose in exile. Moses never set foot in the land he led his people toward.

The Book of Esther appears near the end of the Tanakh and offers a powerful reflection on Jewish life in exile. It stands apart as a story of “man-made” miracles. acts of courage, conviction, and hidden providence that unfold without open divine intervention. Esther reminds us that even in a foreign land, far from the Temple and visibly absent miracles, belief in Hashem and a reconnection to Jewish identity can still lead to redemption. It teaches that exile is not abandonment, and that the yearning to return to Eretz Yisrael, our Promised Land, remains the spiritual compass of our people.

Exile is a state of mind, not a state of place. The Promised Land is a destiny, not a destination. Diaspora is the shared destiny of a people living outside the Promised Land, yet united in their vision of return. Sadly, one can dwell physically in the Promised Land and still feel spiritually exiled.

Exile is the fracture. Diaspora is the thread. The Promised Land is the tapestry still being woven.

From the rivers of Babylon to the deserts of Sinai, from Shushan to Shabbat, we carry not just history but inheritance. The path of our people moves not in straight lines, but in sacred spirals. We are always returning. Always becoming.

There are beautiful contemporary interpretations of the escape from Exile and return to the Promised Land.

In 1978, the Jamaican group The Melodians offered a contemporary interpretation of Psalm 137 through their reggae anthem “Rivers of Babylon.” Later popularized by Boney M., the song transformed ancient verses into a soulful modern lament that captured the ache of exile and the enduring hope of return. It became a spiritual anthem echoing the timeless yearning of the Jewish people to reconnect with their homeland and their heritage.

“By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yeah, we wept, when we remembered Zion… How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” (Psalm 137:1)

“If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her skill.” (Psalm 137:5)

The concept of the Promised Land being something separate from physical space is explained by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel in his book The Sabbath. He describes Shabbat as a “palace in time”—a sanctuary not built in space, but constructed in spirit. In exile, we build not just palaces in time, but cathedrals of memory. Synagogues born from longing.

The question of Diaspora is not whether we are far from the land, but whether we are close to the promise.

In high school, the book Franny and Zooey, by J D Salinger, inspired me. At the end, Franny reminisces about her mom’s delicious chicken soup. It took Franny the entire book (and her life journey) to recognize her mother’s love and how it was embodied in her chicken soup. As they say, chicken soup is the best medicine because it is made with love. In Zooey’s final speech to Franny, she says “You don’t even have sense enough to drink when…Bessie…brings you a cup of consecrated chicken soup. So just tell me, Just tell me…How in hell are you going to recognize a legitimate holy man when you see one if you don’t even know a cup of consecrated chicken soup when it’s right in front of your nose?”

Zooey reminds Franny: the sacred is in your mother’s chicken soup. In your own apartment. In the ordinary, rendered holy through awareness.

After discussing the concepts of the Promised Land, Exile, and Diaspora, I wanted to briefly address the concept of a refugee.

A refugee is not only someone without land, but someone who lacks a shared framework of faith and purpose. They are both geographic and spiritual orphans. To feel like a refugee within one’s own homeland is to suffer spiritual dislocation; what I call geographic dyslexia of the soul. If a people see themselves as refugees while living in a foreign land, it reveals a loss of the spiritual belief that should bind them together as a purposeful Diaspora.

The Jewish people have never been true refugees. Even when forcibly removed from our homeland, we carried the Land of Israel within us in prayer, in practice, and in purpose. Our covenantal connection to Eretz Yisrael transformed exile into dispersion, not abandonment. This is why Jews outside of Israel are not simply scattered. We are the Diaspora: separated in space, but never in spirit.

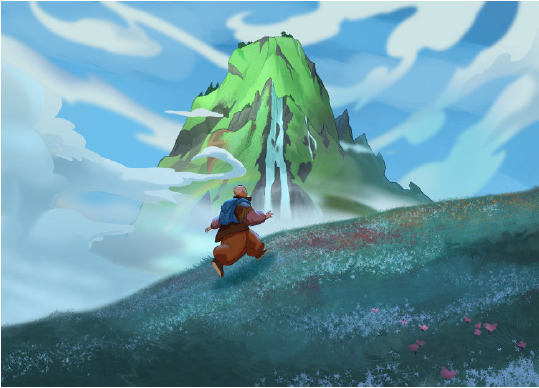

Even exiled, the possibilities of returning to the Promised Land persist. Even Lot, who parted from Abraham, became an ancestor to King David. Even Queen Esther, hidden in exile, preserved the Jewish people. The story does not require perfect place. It requires faithful participation.

Through it all, we remember: We are not merely scattered. We are planted. We are never only exiled. We are always returning.

We are not simply waiting for redemption. We are rehearsing it. We consecrate in palaces in time, altars in exile, sanctuaries in strange lands.

As Eli Wiesel said “When a Jew visits Jerusalem for the first time, it is not the first time; it is a homecoming”

Abraham received God’s inheritance. We continue to believe God’s Promise.

As we recite at the end of each Passover seder each year, “Next Year in Jerusalem”.

Enjoy three haikus inspired by this blog:

Promised land within,

Even far, we face toward home

Scattered, yet rooted.

Rivers far from home,

Time’s palace in exile bloom

Faith builds the land.

Distant lands, one heart,

Jerusalem in each prayer

Diaspora breathes.

This cartoon from my upcoming book, Always a Worm, shows the concept of “Destiny vs. Destination”

Appendix:

Tears of Tammuz:

In the month of Tammuz, we reflect on the Golden Calf. Not only as betrayal, but as spiritual confusion. According to Midrash Tanchuma and Rashi, the idol’s eyes melted, weeping its own falsehood. This symbolizes two types of tears: despair when illusions shatter and longing that draws us back to Hashem and Eretz Yisrael.

I wrote about these here.

Unlike reflex or basal tears, emotional tears contain stress hormones and release endorphins, offering calm after crying. In meditation, I learned that tears can water the seeds of future joy. Even in exile, our tears hold power. One flow marks the collapse of falsehood; the other reawakens our purpose. May your tears nourish your inner garden and help you remember who you are and where you belong.