I always wanted to fly. On my first trip to Morocco, I did.

We traveled there in November 2025, and from the moment we landed I sensed this was not simply another journey but an arrival into something older and more enduring. I had come eager to see the homeland of my life partner, Joan and to truly understand what it means to carry Moroccan Jewish memory as something lived.

On our third morning, we rose before dawn for a hot-air balloon ride outside Marrakech. I was quietly anxious. Flying has always carried a tension for me, balanced between longing and fear. Yet the moment the balloon lifted, the fear dissolved. There was no jolt, no struggle, no sense of conquest. Only an almost imperceptible separation from the earth.

What surprised me most was the silence. We were floating, not forcing. Moving, but never pushing.

Before takeoff, the attendant placed a tray of coffee and French pastries on a narrow board atop the basket. The cups were filled to the rim. I remember thinking this must be a trick, surely it would spill once we were airborne. But as we rose, nothing moved. Not the tray, not the cups, and not even the surface of the coffee.

Suspended in the air, everything remained exactly as it had been on the ground.

Only later did I understand why. A balloon does not fight the wind; it joins it. There is no opposing force, no friction between intention and direction. Cars turn against resistance. Roller coasters thrill us by compressing gravity and speed into conflict. The balloon simply travels with what already exists. When it rises or descends, it does so vertically, cleanly, and effortlessly—guided only by heat and release. One direction at a time. There is no torque nor struggle.

The physics felt like theology.

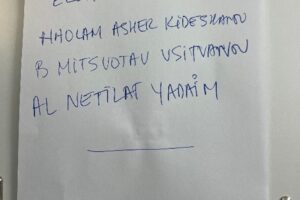

The Torah opens not with effort, but with hovering: “And the spirit of God hovered over the waters” (Genesis 1:2). Before creation takes form, there is movement without force, presence without collision. Later, when the Israelites cross the Sea of Reeds, they do not engineer an escape. They step forward and the water responds. The miracle is not domination of nature, but alignment with it.

Faith in Torah is rarely about certainty. It is about bitachon: trust. Not blind belief, but the courage to move without insisting on control. Trust that the moment will hold. Trust that the ground will appear. Trust that release, rather than resistance, can be a form of strength.

The balloon ride only works because of community: the pilot above, the attendant beside you, and an unseen team on the ground reading the wind, tracking the balloon, and preparing the landing. No one flies alone even when it feels solitary.

That sense of trust deepened for me because of Joan.

Joan is a direct descendant of Baba Sali, Rabbi Yisrael Abuhatzeira (1889–1984), the revered Moroccan-Israeli rabbi whose name still evokes awe and affection among Jews and Muslims alike. For many generations in Morocco, the Abuhatzeira family carried an older teaching, passed quietly across generations, in the form of a story often called the legend of the “Magic Carpet”.

Family tradition traces the origin of the Abuhatzeira name to a story told across generations, most often associated with Rabbi Yaakov Abuhatzeira (1806–1880). According to the legend, when he sought to journey from Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel) toward Morocco without money, passage, or protection, he did not pray for resources or intervention. Instead, he prayed for trust. He was then carried across the sea on a ḥaṣera (a simple woven mat or carpet) an image that later gave rise to the family name Abuhatzeira. In both Hebrew and Arabic, “father” is rendered as אַבָּא (Abba) in Hebrew and أبا (Abā) in Arabic, reflecting a shared Semitic root. The name is often understood as “the father of the mat.” Whether read literally or symbolically, the teaching is the same: the journey was sustained not by means, but by faith.

This story was never meant to be read as fantasy. It functioned as teaching. The “magic carpet” was not an object of power, but a posture of faith: movement made possible not by force, but by alignment; not by control, but by surrender. Jewish tradition calls this bitachon: the courage to move forward without demanding certainty, and to trust that when resistance is released, the way may carry you.

Like Abraham’s Lech Lecha, the story is not about arrival, but about the courage to move before the destination is revealed.

Sitting in that balloon over Morocco, watching my coffee remain perfectly still, sipping without a spill; I understood something quietly profound. I had not learned to fly because I conquered fear. I learned to fly because I stopped resisting movement. Because I trusted the current. Because I trusted Joan. Because I allowed myself, perhaps for the first time, to be carried.

As we entered a new year, I found myself thinking less about what was lost and more about what endured. Wonder endured. Trust endured. The possibility that life can still lift us gently, if we stop bracing for impact.

Faith, I learned, is the courage to move before the path is revealed.

Balloon meets the wind

Nothing pushed, nothing resisted

The sky carries us

“Leap, and the net will appear.”

—-My teacher Cat

Joan and Andy enjoying coffee and croissants among the clouds without spilling

This lived moment of flight echoes an older inheritance—explored in The Magic Carpet Was Never About Flying—and traces back to the Torah’s first call to move before knowing, reflected in They Moved Before They Knew (Lech Lecha). Its quiet wisdom continues in Below the Clouds, where clarity waits beneath what obscures it.